Funders Concerned about AIDS (FCAA) is a philanthropy-serving organization (PSO) founded in 1987 to take bold actions and push philanthropy to respond to HIV/AIDS. They have partnered with AIDSVu to visualize their signature resource tracking report, Philanthropic Support to Address HIV and AIDS. Caterina Gironda is FCAA’s Research & Program Manager, and the report’s primary researcher and author.

What is a philanthropy-serving organization (PSO), and what role does Funders Concerned About AIDS (FCAA) serve in the philanthropic community?

A PSO, also known as a Funder Affinity Group, is a membership organization that often networks, educates, and supports foundations and grant makers. FCAA’s specific mission is to inform, support, and connect HIV-informed funders so they are better equipped to mobilize resources to end the global HIV pandemic as well as build the social, political, and economic commitments necessary to attain health, human rights, and justice for all. We do this by hosting funder meetings that bring grant makers, stakeholders, and, often, activists and advocates from the communities they serve into conversation together.

We also do this through our signature resource tracking report, which gathers and analyzes thousands of HIV-related grants disbursed each year and identifies gaps, trends, and opportunities in HIV-related philanthropy. Even more relevant to the work we are launching here with AIDSVu, we often take these data and do deep-dives that further analyze funding trends among particular populations or geographies. In this case, we have bolstered our data with some additional information that allows us to analyze HIV-related philanthropy to organizations based in the 57 Ending the HIV Epidemic Initiative (EHE) jurisdictions.

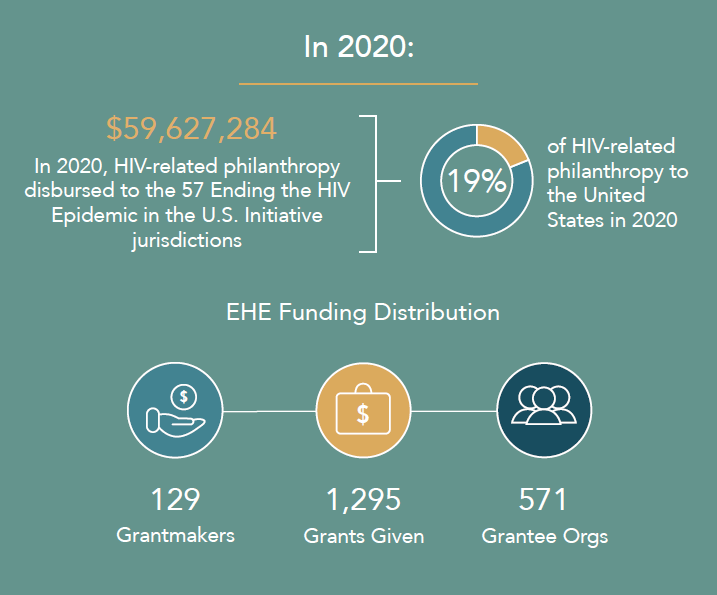

In 2020, approximately $60 million of HIV-related philanthropy was disbursed to the 57 Ending the HIV Epidemic Initiative (EHE) jurisdictions, representing 19% of HIV-related philanthropy in the United States. What do these data tell us about the state of philanthropy regarding EHE programs? Should HIV-related philanthropy be more focused on EHE jurisdictions in the future?

For context, I think it’s key to highlight a few points. While our analysis found that approximately 20% of HIV-related philanthropy in the U.S. is directed to EHE jurisdictions, we are only looking at funding going to organizations doing work at the local or state-level, so this doesn’t account for national or regional efforts that may be contributing to the overall Initiative. We wanted to zoom in on local jurisdictions to understand where efforts were under-resourced.

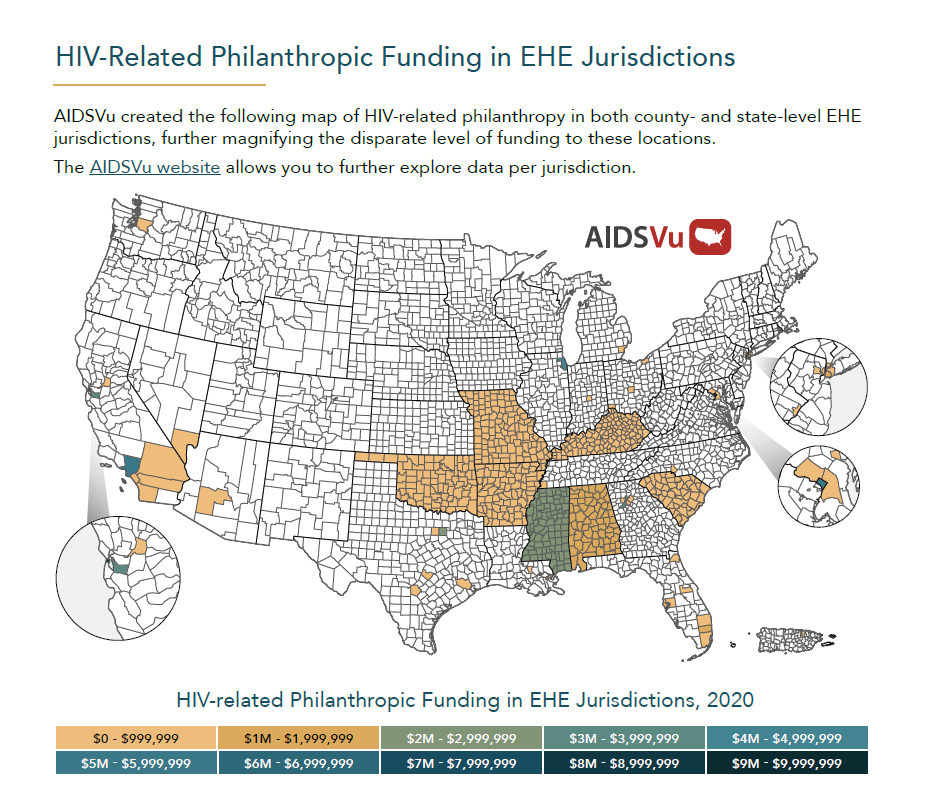

What we found overall is that some areas are receiving little to no support from philanthropy. One of the biggest takeaways is that the vast majority of funding (74%) is going to the top 10 jurisdictions, with the remaining 47 localities receiving just 2% or less.

Knowing this, funders who are more locally and regionally focused — as well as those who may not identify as HIV funders but that are working in ways that intersect with the HIV response — can make better informed decisions.

That is part of why we are so excited about this partnership with AIDSVu: Having a snapshot for local philanthropic funders of what the epidemic looks like in their counties, who it’s impacting, and now, how philanthropy is responding — or not responding — is a powerful tool.

Of course, to end the epidemic in the U.S., we are going to have to continue to increase funding and reach beyond these 57 jurisdictions to every county in the country. It is interesting to think about how we can continue to use the combination of epidemiology data alongside funding data to advocate with private and public funders to ensure all communities are being reached.

What accounts for such a lopsided distribution of HIV philanthropy in EHE counties? How do you think that disparity impacts the lesser-funded jurisdictions’ ability to reach its EHE goals?

Identifying the total level of philanthropic funding to the 57 EHE jurisdictions was the overall goal, but understanding the way that funding is distributed among them is the more interesting finding that really pinpoints one of the key reasons we do these analyses.

We know that the jurisdictions were determined by identifying the 50 local areas that account for more than half of new HIV diagnoses, and then, on top of that, the seven states with a “substantial” rural burden. Historically, the big cities were hit early and hard by the epidemic. But, as a result, the response within cities was often the earliest and quickest as well.

Looking at the distribution of funding, we see San Francisco County with 15%, New York County with 12%, DC and LA with 9%, Cook County (Chicago) with 7%, and so forth. These big cities are understandably home to numerous HIV service organizations doing great work. Many of them have been around for a long time and can handle large grants. And, of course, these are densely populated areas with a large community to support. So, these are not surprising trends.

But when we look at the smaller counties that also have a substantial burden, we see them receiving 2% or less of the funding. Or, when we look at the seven states with high rural burdens, we see that only one, Alabama, appears on that top 10 list. We have seen rural areas, particularly in the South, get left behind consistently over the past 40 years of this epidemic, and now is the opportunity to make progress across the board if we want to end the epidemic in the U.S.

The discrepancies in funding that we are seeing here are important observations that can and should capture the attention of funders. And it should be compelling not just to those interested in and actively funding HIV-related work, but also to community-based foundations in these jurisdictions, or regional funders whose purview includes many of these impacted counties.

As EHE jurisdictions are already receiving federal funding specifically to reach their EHE goals, what role does HIV-related philanthropic funding play in the efforts?

In our annual report, we always center on the fact that philanthropy only contributes 2% of overall funding for HIV in low- and middle-income countries. Now, this is in the context of massive pools of funding — to the tune of 21 billion dollars in 2020 — coming from PEPFAR, the Global Fund, and domestic governments. Here in the U.S., however, philanthropy offers a significant boost to the federal dollars these jurisdictions are receiving. Federal EHE appropriations in 2020 were $267 million, making philanthropic funding to the jurisdictions in that year just under a quarter of that. Beyond just bolstering federal dollars, though, philanthropic funding has the capacity to:

- Offer flexible, unrestricted funding, as opposed to heavily restricted programmatic funding with very low allowances for overhead (we saw during the COVID-19 pandemic how essential this flexibility is);

- Go directly to small and community-led organizations, as opposed to funneling through health departments;

- Have limited reporting burdens, as opposed to notorious government reporting requirements;

- Be used for advocacy purposes, to support policy change, and advocate for more federal dollars; and,

- To reach criminalized populations and conduct work that federal dollars have restrictions against funding.

These are benefits of philanthropic funding that we would tout in any circumstances, not just in the EHE efforts.

We know that philanthropy is, in some cases, helping to support trainings for health departments and communities to collectively ensure their local EHE efforts are community-driven and equitable, and are built to adequately support and reach those most impacted. Communities that have been historically left behind need to be at the center of this work in order for this effort to be successful.

So far, we have not seen significant philanthropic funding specifically earmarked for these types of EHE planning efforts, but we know that it is out there. We hope to see more in our ongoing 2021 data collection.

The new FCAA sections of AIDSVu’s EHE profiles show summaries of HIV-related philanthropic funding in each EHE jurisdiction, breaking down this funding by intended use (such as prevention, treatment, and social services) and by the types of populations that received funding (such as LGBTQ communities). Why is it so important to break down these funding numbers by the communities that received it?

It is important for the transparency of philanthropy in general. Knowing not just that dollars are flowing, but understanding how, and to whom, they flow is at the root of why FCAA does these analyses.

At the most basic level, it is important because grant makers often fund in silos. Seeing these data in the aggregate allows HIV-informed funders to identify if resources are overly concentrated for some strategies or populations, and lacking for others. This type of mapping can lead to concrete change. In 2016 FCAA did a deep-dive analysis of HIV-related philanthropy to the U.S. South. That led to conversations and the initial formation of what is now the Southern HIV Impact Fund, led by AIDS United. It was funders trying to understand where there were duplications and critical gaps, and figuring out, together, how to fund new, exciting, and intersectional work. It is both a resource for funders and an advocacy tool for community members and stakeholders.

Having these data alongside AIDSVu’s snapshots of the epidemic in each jurisdiction brings further clarity to what the needs are for each of these communities and helps to determine if philanthropic funding is being used in the most effective ways.