Frequent Testing for High-Risk Populations

While universal screening provides a foundation for HIV testing, the CDC recognizes that some populations need more frequent testing due to ongoing risk factors. The agency specifically recommends that clinicians screen sexually active men who have sex with men (MSM) for HIV at least once annually, with consideration of even more frequent screening (every 3-6 months) for those at highest risk.

This recommendation is based on extensive research showing that despite seeing primary care physicians regularly, many people at high risk for HIV are not getting tested annually. A recent study highlighted this gap by providing free HIV self-test kits directly to MSM through a public-private partnership. The study found that most participants had either never tested (36%) or had tested more than a year ago (56%), despite many having regular healthcare access. Remarkably, approximately 10% of participants reported accessing additional services including STI testing and PrEP after using the self-test, demonstrating how testing can serve as an entry point to broader HIV prevention services.

The recommendation for frequent testing extends to other populations with ongoing risk factors, including people who inject drugs and their sex partners, persons who exchange sex for money or drugs, sex partners of people with HIV, and heterosexual persons who themselves or whose sex partners have had more than one sex partner since their most recent HIV test. For these populations, annual testing represents a minimum standard, with more frequent testing potentially beneficial depending on individual circumstances and local epidemic patterns.

The Life-Saving Benefits of Early Detection

The benefits of HIV testing extend far beyond simply knowing one’s status. For individuals who test positive, early detection and treatment can be literally life-saving. Clinical trial data sponsored by the National Institutes of Health demonstrate that people diagnosed with HIV early and who start treatment as soon as possible have significantly better health outcomes throughout their lives compared to those who delay treatment.

Modern HIV treatment, known as antiretroviral therapy (ART), has transformed HIV from a fatal disease to a manageable chronic condition for those with access to care. People with HIV who take their medicine daily as prescribed can expect to live nearly normal lifespans and maintain excellent quality of life. Perhaps equally important, consistent treatment that achieves and maintains an undetectable viral load means that people with HIV have effectively no risk of transmitting the virus to HIV-negative partners through sex—a concept known as “undetectable equals untransmittable” or U=U.

For individuals who test negative, HIV testing opens the door to prevention services that are more comprehensive and effective than ever before. This includes access to pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), which can reduce the risk of HIV acquisition by more than 99% when taken consistently. Testing negative also provides an opportunity for healthcare providers to assess ongoing risk factors and provide targeted prevention counseling and services.

Innovations and Accessibility in HIV Testing

The landscape of HIV testing has been transformed by innovations that have made testing more accessible, convenient, and accurate than ever before. These innovations have been particularly important during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, which disrupted traditional healthcare delivery and highlighted the need for flexible testing approaches that can reach people regardless of their ability to access traditional healthcare settings.

HIV testing is now available in an unprecedented variety of settings, reflecting efforts to meet people where they are rather than requiring them to seek testing in traditional clinical environments. Healthcare provider offices and community health centers continue to serve as important testing sites, particularly for routine screening integrated into regular healthcare. However, testing has expanded far beyond these traditional settings to include STD and sexual health clinics, local health departments, family planning clinics, VA medical centers, and substance abuse treatment programs.

The integration of HIV testing into federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) has been particularly important for reaching underserved populations, including people without insurance and those living in medically underserved areas. These community-based healthcare providers often serve as safety nets for populations at higher risk for HIV, making their role in HIV testing particularly crucial.

Emergency department testing programs have emerged as important innovations for reaching people who might not otherwise receive routine healthcare. Emergency departments see large numbers of patients from communities heavily affected by HIV, and testing programs in these settings have identified many previously undiagnosed infections. The emergency department setting also provides opportunities for immediate linkage to care for newly diagnosed individuals.

The Revolution of Self-Testing and At-Home Options

One of the most significant innovations in HIV testing has been the development and expansion of self-testing options, which allow people to test for HIV in private settings without requiring interaction with healthcare providers. The FDA-approved OraQuick In-Home HIV Test, which uses oral fluid, and more recently approved at-home collection kits for laboratory testing have dramatically expanded access to HIV testing.

Self-testing addresses several barriers that can prevent people from getting tested in traditional healthcare settings. These include concerns about privacy and confidentiality, fear of judgment or discrimination from healthcare providers, scheduling difficulties, transportation barriers, and general discomfort with healthcare settings. By allowing people to test in private settings at times convenient for them, self-testing can reach populations that might otherwise remain untested.

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the adoption and distribution of self-testing, as public health agencies recognized the need to maintain HIV testing access even when traditional healthcare services were disrupted. Many jurisdictions expanded self-test distribution programs, including mail-order options and distribution through community-based organizations. These programs have demonstrated that self-testing can be successfully integrated into broader HIV testing strategies while maintaining connections to confirmatory testing and care services for those who test positive.

Telehealth integration has further enhanced the effectiveness of self-testing by providing remote support and counseling to people using at-home tests. This hybrid approach combines the privacy and convenience of self-testing with professional support and guidance, ensuring that people receive appropriate follow-up regardless of their test results.

Community-Based Testing: Meeting People Where They Are

Community-based HIV testing programs have played crucial roles in reaching populations who might not access testing through traditional healthcare settings. These programs, often operated by AIDS service organizations (ASOs), community health centers, and other community-based organizations, provide testing in locations where people live, work, and socialize.

Mobile testing programs bring HIV testing directly to communities, setting up in locations such as community centers, schools, churches, parks, and special events. These programs are particularly effective at reaching young people, communities of color, and other populations that might face barriers to accessing traditional healthcare settings. Mobile testing can also provide culturally competent services delivered by staff who understand the specific needs and concerns of the communities they serve.

Syringe services programs (SSPs) have become increasingly important sites for HIV testing, particularly for people who inject drugs. These programs already serve a population at high risk for HIV and provide trusted, non-judgmental services that make them ideal locations for integrating HIV testing. The combination of harm reduction services with HIV testing and prevention has proven highly effective at identifying undiagnosed infections and connecting people to care.

Pharmacy-based testing represents an emerging innovation that leverages the accessibility and convenience of retail pharmacy locations. Many pharmacies now offer HIV testing services, often provided by trained pharmacists or testing counselors. This approach takes advantage of the fact that pharmacies are widely distributed, have extended hours, and are familiar, non-threatening environments for many people.

Overcoming Barriers and Addressing Disparities

Despite the expansion of testing options and sites, significant barriers to HIV testing persist, particularly for communities most heavily affected by HIV. These barriers operate at multiple levels, from individual concerns about privacy and stigma to structural barriers including cost, transportation, and healthcare access.

Stigma remains one of the most significant barriers to HIV testing, with many people avoiding testing due to fears about potential positive results, concerns about discrimination, or discomfort discussing risk factors with healthcare providers. The normalization of HIV testing through routine screening approaches helps address stigma by treating HIV testing like any other routine medical test. However, targeted efforts are still needed to address stigma in communities where it remains particularly pronounced.

Cost barriers have been significantly reduced through policy changes, particularly the Affordable Care Act requirement that most private insurance plans and all Medicaid expansion programs cover HIV testing without patient cost-sharing. However, people without insurance or with plans that don’t fully cover testing may still face financial barriers. Many testing sites address this by offering free testing, often supported by federal, state, or local funding.

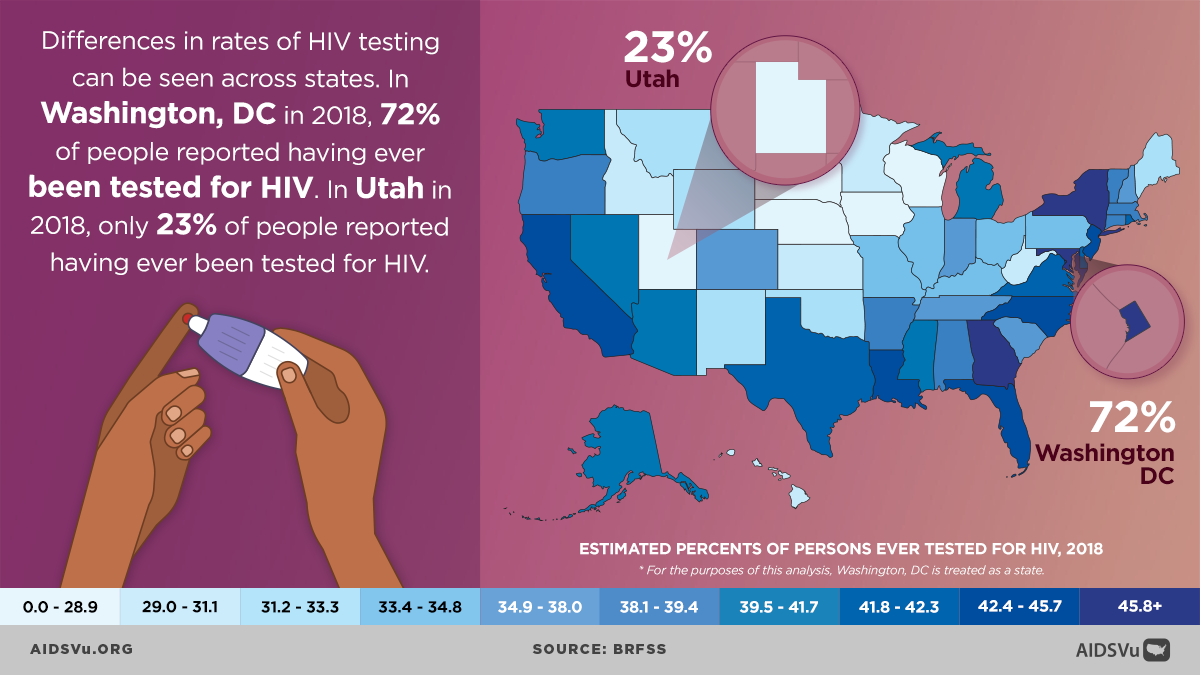

Geographic barriers are particularly challenging in rural areas, where specialized healthcare services may be limited and distances to testing sites may be substantial. Innovative approaches including mobile testing, self-testing distribution, and telehealth-supported testing help address these geographic disparities, but rural communities continue to face unique challenges in accessing HIV testing and related services.

Cultural and linguistic barriers can prevent members of certain communities from accessing HIV testing, particularly when testing sites lack culturally competent staff or materials in appropriate languages. Effective testing programs increasingly recognize the importance of cultural competency and work to ensure that testing services are accessible and appropriate for the communities they serve.

The Testing Process: From Screening to Confirmation

Modern HIV testing uses sophisticated algorithms designed to provide accurate results while minimizing both false positives and false negatives. The current CDC-recommended testing algorithm begins with an HIV antigen/antibody immunoassay that can detect both HIV-1 and HIV-2 antibodies as well as HIV-1 p24 antigen. This combination approach allows for earlier detection of infection compared to antibody-only tests.

When the initial screening test is reactive (positive), a supplemental HIV-1/HIV-2 antibody differentiation immunoassay is performed to distinguish between HIV-1 and HIV-2 infection and to confirm the initial result. If the supplemental test is nonreactive or indeterminate, or if acute HIV infection is suspected, an HIV-1 nucleic acid test (NAT) may be performed to detect viral RNA directly.

This multi-step algorithm is designed to maximize both sensitivity (the ability to correctly identify people with HIV) and specificity (the ability to correctly identify people without HIV). The combination of tests can detect infection as early as 10-14 days after exposure, though the window period can vary among individuals and testing technologies.

Understanding the window period—the time between HIV exposure and when tests can reliably detect infection—is important for both testing providers and individuals being tested. During this window period, a person may have HIV but test negative because their immune system hasn’t yet produced detectable antibodies or because viral levels aren’t yet high enough to detect. This is why people with recent potential exposure may need repeat testing and why providers may recommend HIV RNA testing if acute infection is suspected.

Integration with Prevention and Care Services

Effective HIV testing programs recognize that testing is just the beginning of a person’s interaction with HIV prevention and care services. For people who test negative, testing provides an opportunity to assess ongoing risk factors and connect them with appropriate prevention services, including PrEP for those at high risk.

Prevention counseling has evolved from lengthy, formal sessions to brief, focused conversations that help people understand their results and identify strategies for staying HIV-negative. This approach recognizes that most people receiving negative test results don’t need extensive counseling but can benefit from basic information about HIV prevention and available services.

For people who test positive, immediate connection to care is crucial for both individual health outcomes and prevention benefits. Effective testing programs have systems in place to ensure that people with positive test results are quickly linked to HIV medical care, ideally within days rather than weeks. This rapid linkage helps ensure that people start treatment as soon as possible, improving their health outcomes and reducing the time during which they might unknowingly transmit HIV to others.

Partner services, also known as contact tracing, represent another important component of comprehensive HIV testing programs. When someone is newly diagnosed with HIV, partner services programs work with them to identify recent sexual or needle-sharing partners who may have been exposed to HIV. These partners can then be offered confidential testing and, if positive, immediate linkage to care, or if negative, prevention services including PrEP.