Lindsey Dawson, MPP, is Associate Director of HIV Policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF)

You have spent your career at the intersection of HIV and health insurance coverage. What led you to this focus?

What drew me to the HIV side of health policy was the complexity of the policy issues, the rapidly evolving science, and a desire to work at the deepest recesses of health disparity. After living there for several years, I received my Master’s in Public Policy (MPP) in London and focused on health policy. At the time, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) had just been signed into law in the U.S. and I saw this as an exciting opportunity to return to the states and work on policy issues related to health systems change.

I’ve also found that there’s something unique about the policy community surrounding HIV – it sits somewhere in-between academia and activism. There is a rich history within this community and since the early days of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, diverse groups have come together to improve health equity and advance policy goals. It was important for me to work on an issue that affects marginalized communities. There are disparities across all areas of health, but they are especially prevalent with HIV. This field is multifaceted, and the policy environment is complex due to the various disparities that drive the epidemic, but it is the diversity of the HIV policy community that drew me in and has kept me engaged in this important work.

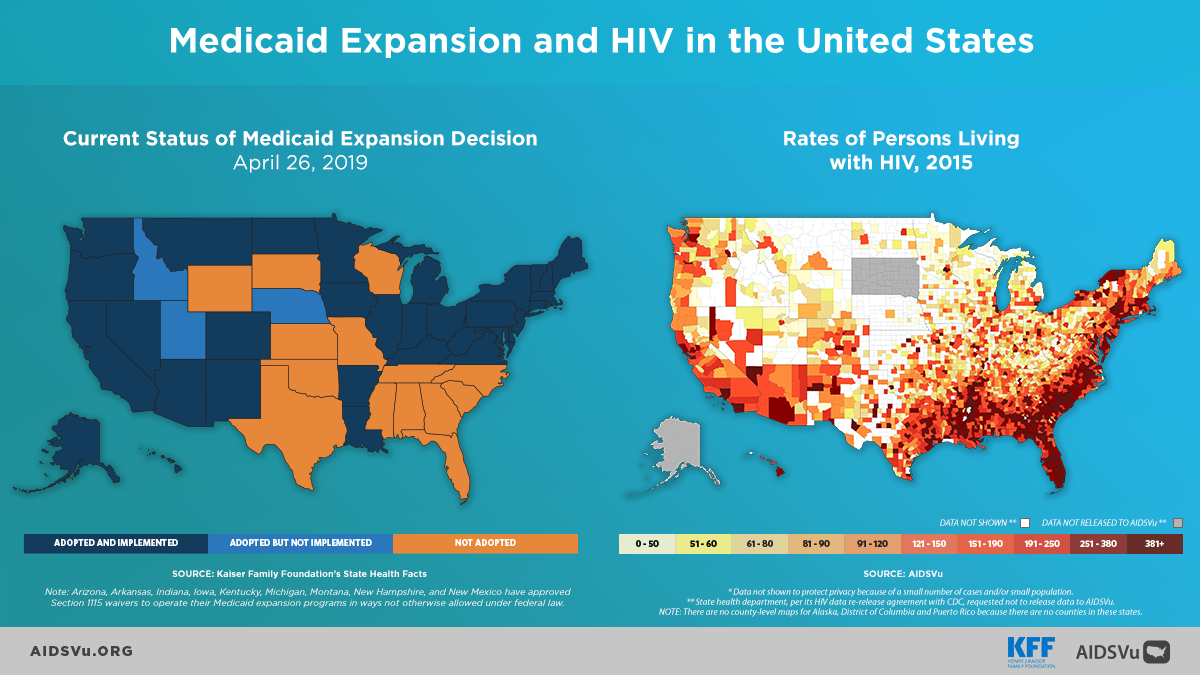

At KFF, you have examined the impact of Medicaid expansion on people living with HIV and other infectious diseases. What changes have you observed since the implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), especially in states that opted to expand Medicaid?

Following the implementation of the ACA coverage expansions in 2014, we were able to track how Medicaid expansion affected people with HIV from both qualitative and quantitative perspectives.

- On the quantitative side, we examined insurance coverage changes among people with HIV under the ACA using the CDC Medical Monitoring Project surveillance data. We found that Medicaid coverage among people with HIV increased nationwide from 36 percent in 2012 to 42 percent in 2014. Notably, these coverage gains were driven by people in states sampled that expanded Medicaid. In these states alone, coverage jumped from 39 percent to 51 percent between 2012 and 2014, and the rate of uninsured fell from 13 percent to 7 percent.

- To provide more quantitative data, in collaboration with CDC, we observed that viral suppression, the ultimate goal of HIV treatment, increased by 8 percent in Medicaid expansion states from 2012 to 2014. There was no causation attributed in this study, but we observed the correlation in the relationship during the time of the policy implementation.

Qualitative data is important because by talking with people impacted by the coverage changes, we are better able to understand gaps and trends in the data. For example, in 2014, we spoke to people in Medicaid expansion states and non-Medicaid expansion states and found that overall most individuals’ HIV care needs continued to be met. In expansion states, this was primarily occurring through new access to Medicaid. These individuals were able to meet a broad range of health needs, including HIV. For example, some were not only receiving HIV treatment but also were now getting care for diabetes, and others were in physical therapy for the first time. In non-expansion states, however, it was a different story. People with HIV continued to meet HIV care needs through the Ryan White Program, which many called a “lifeline;” but at the same time, they were going without care for other health conditions. We heard a great deal from people in non-expansion states who were worried about their health and economic security and felt great frustration that their elected representatives decided not to expand their Medicaid program.

President Trump’s recent funding requests for a new Ending the Epidemic plan have placed HIV more directly in the public spotlight, but many advocacy organizations are still skeptical. What are your thoughts on how best to monitor the new program’s outcomes, and what actions can we take to ensure that the connection between the opioid epidemic and viral infections like HIV and Hepatitis C remain a priority for both policymakers and the general public?

To Make investments and monitor within targeted jurisdictions would allow for consistency in reporting progress towards the initiative’s goal of reducing new infections. Monitoring should also help us assess what is working, what isn’t, and where greater investment needs to be made. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) will be releasing specific indicators to aid in this process and align them with the National HIV/AIDS Strategy, to the extent possible. This alignment is important as it removes some reporting burden so that public health officials can spend more time on areas addressing the epidemic on the ground and less time reporting.

Jurisdictions may also need to identify metrics specific to their own localized epidemic within their local planning. For example, if the county is experiencing a significant number of new infections resulting from injection drug use, they could implement a specific metric to capture those new infections and other related infectious diseases that can be transmitted through injection drug use and needle sharing.

In terms of maintaining a connection between the opioid epidemic, HIV, and Hepatitis C, without additional harm reduction resources, we can expect to see more cases of HIV and Hepatitis C associated with injection drug use. Historically, the decline in HIV infections associated with injection drug use has been a major success in the fight against HIV in the U.S. From 1990 to 2015, we saw HIV infections attributed to injection drug use fall from 40 percent to 6 percent. While that is a significant success story, the current opioid epidemic does threaten to undermine or reverse some of this progress.

KFF has noted that of the 220 counties identified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as vulnerable to an HIV or Hepatitis C outbreak, just 24 have syringe service programs (SSPs). What does that mean for these vulnerable populations and public health advocates?

These 24 SSPs are the only ones that have been reported to the North American Syringe Exchange Network (NASEN); it is possible that there are other programs, but it’s meaningful that just 11 percent of these counties have easily identifiable programs. That raises public health and public policy concerns and underscores communities’ vulnerability –there is less access to a very important tool in the prevention toolbox.

Notably, CDC recently released its HIV Prevention Progress Report for 2019 and found no progress on its non-sterile injections target, which is to reduce the percentage of HIV-negative persons who inject drugs using non-sterile injection equipment by at least 25 percent. In fact, from 2012 to 2015, this percentage remained stable at 61 percent. That we do not see a reversal in this trend is especially stark against the backdrop of the opioid epidemic. It’s important to remember that in many cases SSPs are not just a place to exchange syringes but are more comprehensive programs. They provide drug-using communities access to testing, care, support, and if desired, linkage to addiction treatment.

For public health advocates and officials, this all means that there is significant work to be done to reverse the trends. This could mean addressing vulnerabilities through local policy change, an environmental change, having new conversations to change local perspectives, or ramping up investment. In some cases, a formal policy change at the state level might be required. For instance, sixteen states would require legislative action to implement an SSP. Beyond SSPs, there are other approaches to address this policy challenge on the table. For instance, jurisdictions could explore whether naloxone is provided to first responders and others in drug-using communities. Another consideration is access to medication-assisted treatment (MAT). KFF colleagues on the Medicaid team assessed the role that health centers play in overdose prevention, and, among the health centers sampled, 48 percent provide Medicaid-assisted treatment, and roughly 40 percent supply naloxone. As such, health centers’ roles could be further examined in light of the Ending the Epidemic initiative.

HepVu recently added three opioid indicator maps to the site. How does visualizing data help us better understand and respond to the syndemic of opioid use, Hepatitis C, and HIV?

Broadly speaking, AIDSVu and HepVu have made complex data visual and digestible. There are tables rich with epidemiological and statistical data that are great for researchers, but they are challenging to glance at to obtain a nationwide “snapshot” or understanding of a particular issue or indicator. AIDSVu and HepVu bridge this gap in data presentation.

One aspect of the HepVu and AIDSVu that is particularly helpful is the ability to compare indicators across HIV, viral hepatitis, and the opioid epidemic, along with other social determinants of health indicators. Data visualization helps us to better convey policy problems and improve our storytelling, whether for researchers, policymakers, or media.