Noah Mancuso is a PhD student and Laney Graduate School Fellow at the Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University. Mancuso founded the Queer Health Collaborative (QHC), a health consulting company focused on improving the quality of healthcare for LGBTQ+ individuals through inclusion in research. Recently, Mancuso has been working on research regarding the drive time to local PrEP clinics.

Q: Recently, you have been working on research that maps drive time to the nearest PrEP clinic. Why did you choose to research this topic, and what have you found so far?

One of the motivations for this research is trying to better understand PrEP access and what PrEP access means – not only if people can afford it or know about it. Drive times are a measure of if someone can physically go get PrEP–it’s a matter of access. This analysis was done almost eight years ago, but a lot has changed in that short time frame. We were curious to see how drive times have changed, and to see what progress we’ve made in the field in improving physical access, and to examine how we can improve access even more.

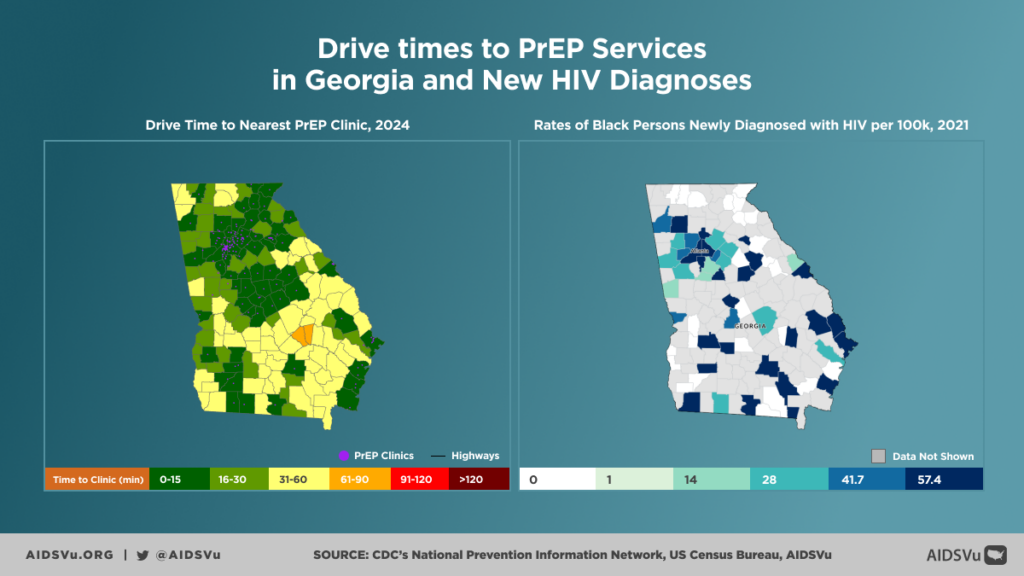

We found that there have been many improvements like shorter drive times, which is great. The shorter drive times can be attributed to an increase in the number of clinics and easier drivability to those clinics. But we still see a lot of the same disparities in drive times across the country. More rural places often have drive times up to two hours or longer, just for one way, which is really not accessible for anyone. Additionally, we’ve found some similarities with other work about PrEP utilization in terms of states that have expanded Medicaid or implemented PrEP DAP programs — they have more clinics and lower drive times, which just means easier access to PrEP.

Q: Your drive time maps in Georgia show minimal drive times in most Northern areas of the state, but longer drive times in the Southern parts of the state. Why do you think this drive time discrepancy exists?

Georgia mirrors national trends. Urban areas have more clinics, and thus shorter drive times. We see it in metro Atlanta, the Savannah region, and several other areas due to urban population densities. There is quite a bit of overlap with political leaning, as well. Areas of the state that are more populous are more left-leaning, and that generally means that those areas are more open to sexual and reproductive health services. There’s more access to specific clinics, and the providers themselves are more willing to prescribe PrEP. Since you don’t need a specialization, technically any doctor can prescribe it, so people who do are more likely to be in urban parts of the state.

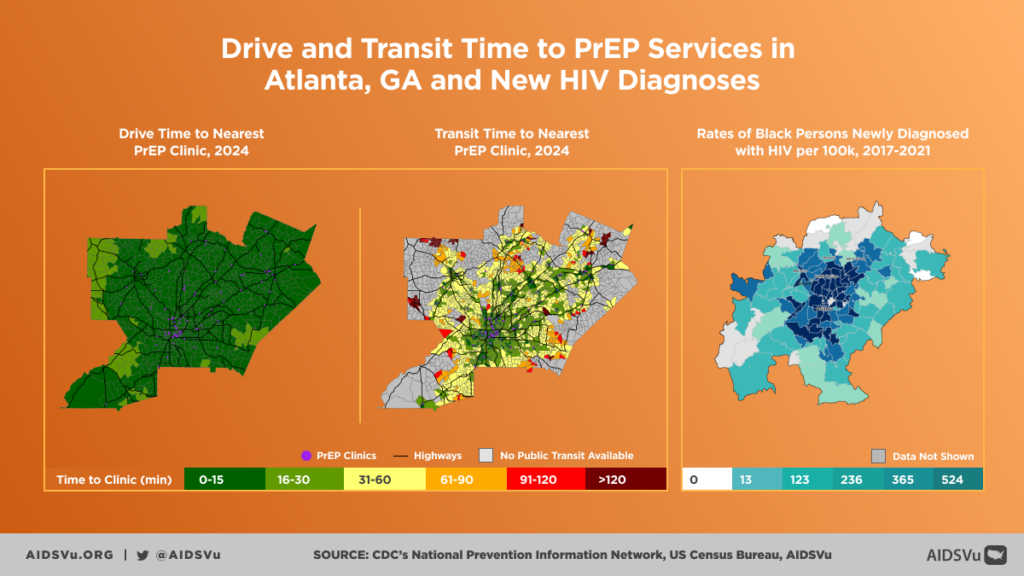

Q: Another aspect of your current research includes mapping transit time to the nearest PrEP clinic. In your Atlanta transit map, it is clear that most PrEP clinics are concentrated in one area of the city. What are the implications for the transit time map and PrEP equity in Atlanta?

The motivation to analyze transit time accounts for the fact that not everyone has a car. There’s a lot of inequitable access surrounding those who can afford private vehicles or even ride sharing platforms. A lot of individuals are reliant on public transit, because they don’t have physical access to a car. For these individuals, drive times don’t mean anything. A lot of the priority populations for HIV prevention are disproportionately dependent on public transit. The transit time analysis set out to examine how accessible clinics are to people who rely on public transportation. We specifically chose to examine Atlanta as a test case – to see how the methods worked and how insightful they were. We expected areas that are more populous, like downtown Atlanta, to have more clinics, and that’s also where a lot of the public transit stops are. The MARTA trains and buses go there, but in the more suburban areas of Atlanta, there’s not as great access to public transit.

So far, there are good signs in our findings. We see a lot of overlap in Atlanta with the HIV prevention priority populations, so areas of Atlanta that have a higher proportion of black or African American individuals, Hispanic and Latinx individuals, people living below the poverty line, and younger individuals. We’re also finding better access via public transit in Atlanta. We’re meeting a lot of the population where they are, but over 50% of the census blocks that we looked at don’t have public transit at all. Even though there has been progress made, there are still a lot of people who don’t have access to PrEP but could probably benefit from it.

Drive times and transit times are translatable not only to PrEP clinics, but also where antiretroviral therapy (ART), mental health services, substance use programs, and a plethora of other services are being provided. This analysis can be used more holistically for HIV prevention and in general, to understand LGBTQ+ health and what access means on a community level.

Q: You recently founded Queer Health Collaborative (QHC), a consulting company with a mission to increase LGBTQ+ representation in public health research. Why did you choose to start this company, and what are your goals for QHC’s success?

Working in the HIV field and public health in general for the past few years, a lot of the work I’ve participated in relates to health inequities among the LGBTQ+ community. Most of the researchers have great intentions behind their work, but don’t identify with or belong to that community. That lack of identification resulted in disconnects with the research aims, misrepresentation of the community, lack of translation of our findings, and overall general bias in how we looked at data. As a young professional going back to get my master’s degree and now PhD, I wanted to find a way to get our community more involved in that work.

QHC started as a student-led group. I knew a bunch of other master’s students who identified as LGBTQ+, and we found some professors at Emory who were working with the community and wanted some more insight. We’re working on a ton of projects right now. Seeing those through the finish and getting young queer people the recognition for the work that they’ve done, whether that’s publications with their name on it or leading presentations, is a great measure of success. Down the road, if we’re able to start measuring the impact that we’re having, that would be great. A huge part of the motivation behind this was that minority individuals were doing a lot of the community outreach and educational work for free. It’s just expected of them to educate others. A cool aspect of this has been being able to compensate people for their knowledge, familiarity, and work they do every day. Right now it’s all part-time, but being able to do that full time or paying someone full time would be a great way to measure the success of QHC.

Q: What is one message you would like to share with the LGBTQ+ community surrounding PrEP use and PrEP equity?

We can’t end the HIV epidemic without using tools like PrEP, which we know is 99% effective when taken correctly. And everyone should have the right to access PrEP without stigma and without financial burden.

PrEP isn’t just for cis, white, gay men. A lot of people can benefit from it. The LGBTQ+ community is probably already aware of equity issues related to access, so it’s on public health officials and policymakers to expand access and address equity, whether through state and national PrEP programs, PrEP DAP programs or Medicaid expansion. There’s the PrEP Access and Coverage Act that was introduced in Congress. On a local scale, we can combine PrEP services with pharmacy programs or substance use programs. Ultimately, there’s a lot that we can be doing as a public health community to help the LGBTQ+ community and others who are vulnerable to HIV better access PrEP.