In observance of Southern HIV/AIDS Awareness Day, AIDSVu spoke with the Director of Health Department Initiatives at Southern AIDS Coalition: Darnell Barrington, MPH.

Q: You began your position as Director of Health Department Initiatives at Southern AIDS Coalition (SAC) back in 2020. What drew you to this work and what types of initiatives have you found to be most effective at addressing the HIV epidemic in the South?

Honestly, the sense of community drew me to this work. I like to present myself in my truth. My truth, at one time in my life, was that I was a poor little Black gay boy from Norfolk, Virginia. It is those identities and experiences that allow me to come into spaces and affect change by advocating for systemic changes in HIV prevention and care for those most impacted. This is my community.

In terms of initiatives, the most effective approach is to always maintain client centeredness and keep the community at the core of everything that that is being done to address the HIV epidemic. There is nothing about this work that happens without the people that are among the most impacted, including Black women, MSM or Same Gender Loving Men, and people of trans experience. These are the people that must remain at the center of everything that happens with our work with HIV and AIDS.

Q: You have stated that the narrative around HIV in the South is “outdated.” In your opinion, what is a better narrative for the presence of HIV in the South? What are some misunderstandings about the region’s approaches to HIV care?

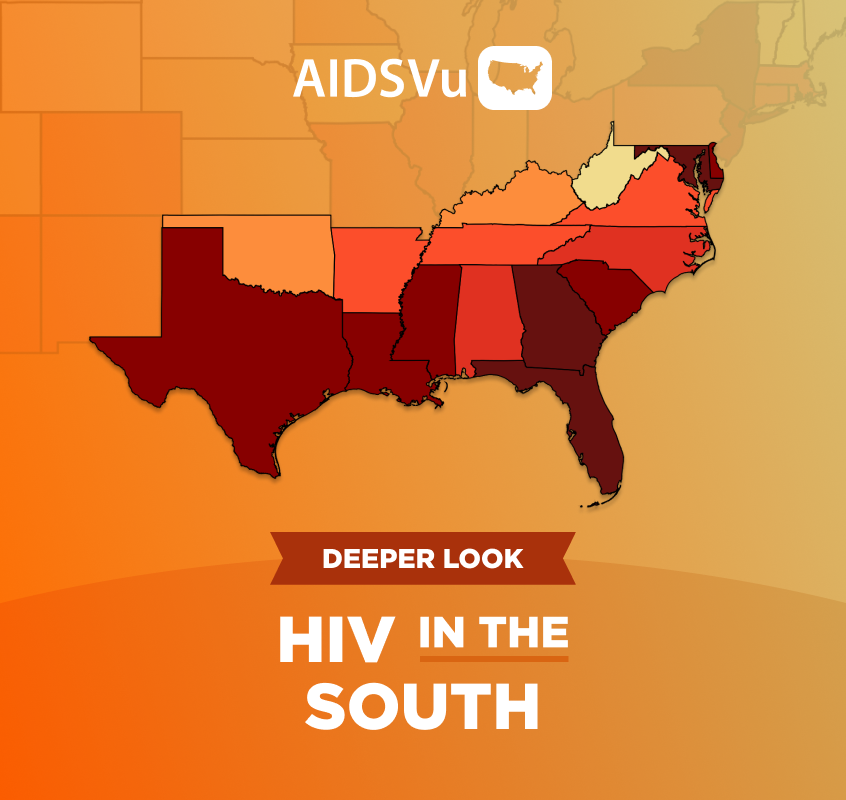

I truly believe that the solution to ending the epidemic on a national scale will be found in the South. The South is such a cradle of innovation where so many of the answers exist, but where people are not always invited to the table. This is the new narrative: the South is fully capable of addressing the needs of people living with HIV or at increased risk for HIV, but it needs opportunities for people’s voices to be heard and opportunities to advocate so that there are adequate resources and funding.

Q: In your effort to coordinate HIV care with health departments across the country, what problems do you find that these organizations regularly come across? What obstacles are preventing them from moving forward with innovations in care?

There are many strategies that we could use that have been voiced, but many are subject to certain political hurdles that stop these strategies dead in their tracks. Unfortunately, the powers that be are often represented by those least impacted by the progressive policies and innovative strategies that will address the HIV epidemic. Many of these issues are interconnected, so I will also add that funding is an issue. Funding is an issue, particularly equity in funding, because those who need the most support, rural communities and communities of color, are the people who are most often overlooked.

Lastly, an adequately representative workforce is necessary. Something as simple as hiring a transgender outreach specialist, for example, or a man who has sex with men (MSM) as an outreach specialist is often met with resistance. We know that these are communities that are deeply impacted by HIV, but then there are inequitable hiring practices or there is never any funding to ensure that key positions are staffed by people who would be the best at engaging these communities. People with specific life experiences and perspectives can absolutely make a meaningful impact, but they are often not given the chance.

Q: In the past, you asserted that bringing “a culture of care” is essential to servicing HIV/AIDS needs in the South. Can you expand on what your ideal HIV care infrastructure would look like if you had all the necessary resources?

We often think about prevention as PrEP and condoms, or we think about treatment as just taking a pill a day, and that’s it. Comprehensive care involves so much more than that. Even when we are successful in increasing access to medication, there is so much more that goes into supporting one’s adherence to treatment or viral suppression. We must put more emphasis on not only social determinants of health, but also on psychosocial support and building stigma-free support networks for those impacted.

In the wake of COVID-19, we have had to reorient ourselves within the HIV workforce to reconsider how we offer care. That culture of care must include the entire HIV ecosystem: everyone from our federal partners to our community health workers has a responsibility in applying this culture of care so that every person living with HIV is taken care of. I applaud the United States federal government for officially adopting U=U (Undetectable equals Untransmittable) as a national mantra to guide HIV treatment and prevention efforts. This is a step in the right direction.

Q: August 20 is Southern HIV/AIDS Awareness Day (SHAAD). What message do you have for the community on this day?

I am so excited about Southern HIV/AIDS Awareness Day. Southern HIV/AIDS Awareness Day is about so much more than testing. SHAAD is about embracing the community and everything that the South possesses to address the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Most importantly, this is a day to be proud: It’s about being proud to be a Southerner and being proud to take part in your health and the health of your community.