Vincent Guilamo-Ramos, PhD, MPH, LCSW, RN, ANP-BC, PMHNP-BC, FAAN, is Dean and Distinguished Professor of the Duke University School of Nursing and Vice Chancellor for Nursing Affairs, Duke University. In addition, he is the founding director of the Center for Latino Adolescent and Family Health (CLAFH) at Duke University.

Your research and work as a nurse practitioner have focused on adolescent reproductive health, including HIV. What drew you to this focus?

I think what really drew me to this focus was growing up in the South Bronx, in New York City. In the neighborhood where I grew up, there were many young people that were similar to young people all over New York City and across the United States. Despite being similar, I noticed that there were different outcomes, that there were higher rates of unplanned pregnancies, and that sexually transmitted infections were more common. In addition, I noticed in the late 1980s and early 90s that people living with HIV was becoming more common in my neighborhood.

As a Latino gay man, I knew young people of color living with HIV, and in some cases AIDS. I remember having a friend who was a young Latino gay man who was living with AIDS. These experiences made this an issue that is near and dear to me. In sexual reproductive health, particularly HIV, your work intersects with social determinants of health, social justice, and the health equity issues that surround the epidemic. Those are themes that have always been very present in my own way of viewing my life and the work that I do.

Your recent paper in The Lancet HIV “Is the USA on track to end the HIV epidemic?” discusses how, while overall HIV infections have reduced by 19% between 2010 and 2021, for certain communities new HIV infections are decreasing too slowly, stagnating, or in some cases increasing. What communities did you identify as being “left behind” through your research?

For context, my paper focuses on tracking the progress of the Ending the HIV Epidemic Initiative (EHE) under the current federal plan, and whether current trends in HIV prevention and treatment will allow us to meet our goal of ending the epidemic in the US by 2030. To start, I do not in any way want to suggest that all that work over the past four decades hasn’t resulted in major improvements. One thing that has been apparent for some time now is that many fewer individuals are in the hospital due to AIDS—at least in the US—and that the young people who would have potentially been hospitalized are growing up and pursuing meaningful lives as a person living with HIV.

That progress is amazing, and something that we should be proud of. At the same time, despite messaging highlighting all of our successes, less focus has been placed on where there has been inequitable progress.

There are some groups that have made progress—the number of new infections each year has gone down. One great example of progress is within the African American community, although that rate of progress is still too slow. It is still the case that, relative to other racial/ethnic groups, African Americans have the highest HIV incidence. So, while it represents progress, the numbers are still unacceptably high.

When I think about my own community, the Latino community, this is something that has been largely invisible—and I’m intentionally using that word—invisible. For more than a decade, cases have largely remained steady among Latinos and that is alarming. In other words, there has been a 0 percent decrease in annual HIV incidence in the Latino community between 2010 and 2021, compared to a 19% decrease overall. The plain truth is that HIV prevention and treatment in the U.S. is inadequately meeting the needs of the Latino community.

We also see that among Black and the Latino young men who have sex with men (MSM), there have been dramatic increases in terms of estimated new HIV infections. Specifically, the estimated number of annual new infections had increased by about two thirds for both Black and Latino young MSM between 2010 and 2021.That is simply not acceptable given the tools that we have. It suggests that the tools we have are not reaching the right populations consistently. It means that there are systemic failures where we are not able to implement all the available prevention and treatment options in a way that would prevent that forward transmission. This means that we need to take a step back and redouble our efforts. If we are going to meet the established Ending the HIV Epidemic (EHE) goals for 2030, then we are going to need to do some things differently. We created two user-friendly resources to help spread the word regarding how best to increase the chances of ending the HIV epidemic by 2030. You can view the brief video and flipbook here.

One finding that stood out is that more than one in four Latina and Black transgender women are estimated to be living with HIV. What can we do to better elevate their needs and connect this vulnerable population to prevention and treatment services?

I deeply respect the transgender community because of all their incredible advocacy. Transgender individuals have been fighting for their lives and fighting to be seen and have their needs met. I think the major reason for these disparities is the invisibility and the stigma associated with the transgender community. I think that insurance at a policy level is not providing coverage for the full range of sexual and reproductive health services, including gender-affirming treatments, that the transgender community needs.

In addition, the lack of transgender people in important leadership roles, including roles at the forefront of prevention or treatment programs, is part of the problem. I think that also extends to policy. Very rarely do we have transgender individuals in significant leadership roles. It matters to have somebody who is publicly serving in leadership at a very high level, who is raising awareness around the contributions of transgender people for everyone.

Finally, if we are to reach any of the communities disproportionately impacted by HIV, we need to address the social conditions that drive health disparities. If we cannot address compounding social issues like unemployment, lack of health insurance, racism, homophobia, or transphobia, we will not be able to reach the goals laid out in the EHE initiative. To be clear, we need new thinking on how best to address the harmful social determinants of health in the U.S. Recent examples from the nursing profession highlight promising new approaches, such as the DUSONtrailbalzer.

Another statistic shows that between 2010 and 2021, the estimated annual HIV incidence for young Hispanic/Latinx men who have sex with men (MSM) increased by 65%, while during the same period HIV incidence fell among young White MSM by 5%. What factors shape this alarming disparity?

We are not just failing young Hispanic/Latinx MSM, we are failing young MSM as a whole. It should be a national emergency that the prevalence numbers we cite in the paper are this high, and it is completely unacceptable that young people will be starting their adult lives living with HIV, and that these numbers continue to go up despite the progress we have made overall.

We must recognize that young people do better in what we call youth-friendly services. Youth-friendly HIV prevention and treatment healthcare services specifically address the developmental needs of young people. What is also true is that much of our prevention and treatment infrastructure is missing the very populations that are experiencing dramatic increases in incidence, like young MSM of color. We are inadequately reaching them for testing, prevention, and treatment. We struggle with sustaining their viral suppression. On every indicator, whether it is HIV testing, PrEP uptake or treatment outcomes along the care continuum, young people fare much worse relative to their adult counterparts.

That suggests that the system for delivery of HIV prevention and treatment needs to look different for young people. We know that when we have youth-focused programs, outcomes tend to improve significantly because they incorporate youth-friendly services, including wraparound services, that are tailored to the needs of young people.

Your paper concluded that “without implementation of an equitable national HIV response, we cannot sufficiently accelerate progress in the remaining 7 years to achieve the goal [of ending the HIV epidemic in the US] by 2030.” Can you tell us more about what an equitable national HIV response should look like?

The overall picture is certainly more complicated than what I’m going to highlight, but for the sake of having a succinct explanation, I think first and foremost we must prioritize public health prevention and health promotion. Right now, most of the money that we spend in healthcare is focused on treatment of existing conditions and not prevention. The truth of the matter is that as a country, we should be investing much more in preventing illnesses as opposed to solely treating them. That is the number one priority: making it clear that an equitable healthcare system means investing in public health and health promotion and prevention.

Number two, I would say that we need to address issues with the public health workforce. Too long our workforce has been primarily biomedical. We’ve tended to focus heavily on infectious disease doctors, without adequate attention to other important care team members, including nurse practitioners, nurses, physician assistants, and pharmacists. We must think about a workforce that includes both clinical and nonclinical roles, includes people with lived experience of HIV, and includes mental health and addiction specialists. I think an equitable health system means leveraging a broadened workforce that is diverse and that is inclusive in terms of ethnicity, race, identity, and profession. These ideas should be at the forefront of our efforts towards ending the epidemic.

The third piece is stigma, which is a huge issue in the context of HIV. We must recognize as a country that until we have hard conversations about sexual and reproductive health and make it a household conversation that every family is having, people living with or at risk for HIV are going to continue to experience shame, blame, or a sense of societal alienation and discrimination. Unfortunately, there are too few resources supporting young people living with HIV to reduce HIV-related stigma. That is why a group of us created NO FEARS. NO FEARS is an animated story of a Latino young man living with HIV and grappling with how to reduce stigma with the help of his family.

The last thing I would say is that we need to think about the social determinants of health that drive health disparities. We cannot just focus on clinical care. It is very clear to me when I am working with a young person that 80% of the battle is about things that are happening in their life outside of the encounter and outside of things that I can immediately touch with clinical care. It needs to be an entire system—their schools, families, community-based organizations—that is supporting this individual and all of us to maintain and to prevent negative health outcomes.

In July, the House Subcommittee on Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies (LHHS) proposed an appropriations bill that eliminates funding for the Ending the HIV Epidemic Initiative (EHE) at the CDC. From your perspective, how would this proposed bill impact our progress towards ending the epidemic by 2030?

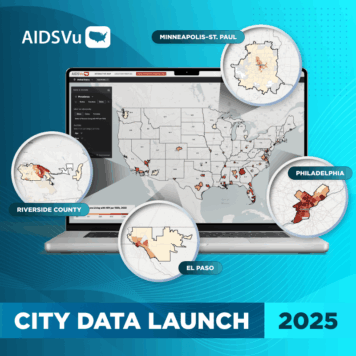

This is simply terrible. The US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) launched the Ending the HIV Epidemic in the US (EHE) initiative in 2019. The initiative aims to reduce new HIV infections in the U.S. by 90% by 2030 by scaling up key HIV prevention and treatment strategies. What is unique about this initiative is that it targets the 48 counties and seven states that account for more than half of new HIV diagnoses. Thank goodness we prioritized geographies with elevated HIV incidence, because it gave us a blueprint of how we could prioritize our prevention and treatment services.

It is very obvious that during the years the EHE program was in place (prior to COVID) that on average the numbers of new HIV infections dramatically decreased. So, it appears that the program is working. That does not mean that we can’t do more and that we don’t need to amplify and escalate our efforts, but a U.S. without a focused program for ending the HIV epidemic would mean that we could potentially revert to where we were prior to the program. And so, to me, it is a scary thing to think about.

If the federal government were to ask me about the next iteration of EHE, I would say that we are on the right track. We have made progress, but this is the perfect moment to look at the fact that we have had inequitable progress. We need to think about zooming in on those populations that have been left behind.