Aaron Siegler, PhD, MPH, is the Director of Geospatial Core and an Associate Professor in the Department of Behavioral Sciences and Health Education at Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health.

The Gilead COMPASS Initiative™ (COMmitment to Partnership in Addressing HIV/AIDS in Southern States) is a 10-year, $100 million commitment to support organizations working to address the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the Southern United States.

Q: You work in the COMPASS (COMmitment to Partnership in Addressing HIV/AIDS in Southern States) Initiative™ as a director in the capacity building area. What are the goals of the COMPASS Initiative?

The goals of the COMPASS Initiative are to work with community partners to find evidence-based solutions to support the needs of people living with HIV. We do that through a number of mechanisms. First, we provide grant support for local organizations that provide health care services to people living with HIV. Second, we have capacity building and training opportunities for local organizations that are committed to providing high-quality services to those most impacted by HIV. Another part of the initiative is looking to address disparities within the HIV epidemic through innovative approaches like reducing stigma and promoting well-being, mental health, and trauma-informed care.

Q: As the Director of Geospatial Core, what is your mission?

The mission of our core is to provide evidence regarding geospatial access to services that are supported by the COMPASS Initiative. This is exciting because it includes services that were previously overlooked, such as stigma mitigation interventions, as well as services that were previously less explored, like trauma-informed care. In addition, this includes services that need to be addressed in a more nuanced way. One example is increasing the availability of mental health services for people living with HIV.

In our view, it’s essential that people living with HIV have high-quality access to services that facilitate their health. At the Geospatial Core, our data should be used to inform our understanding of where current service provision may be lacking, which allows us to efficiently guide the COMPASS Initiative as well as the work of the broader community. For example, our team can help identify service deserts that can then inform our community partners on how to better allocate resources and other support services.

Q: One of the things that you talk about is service deserts. What is a service desert and why is mapping them an important part of COMPASS?

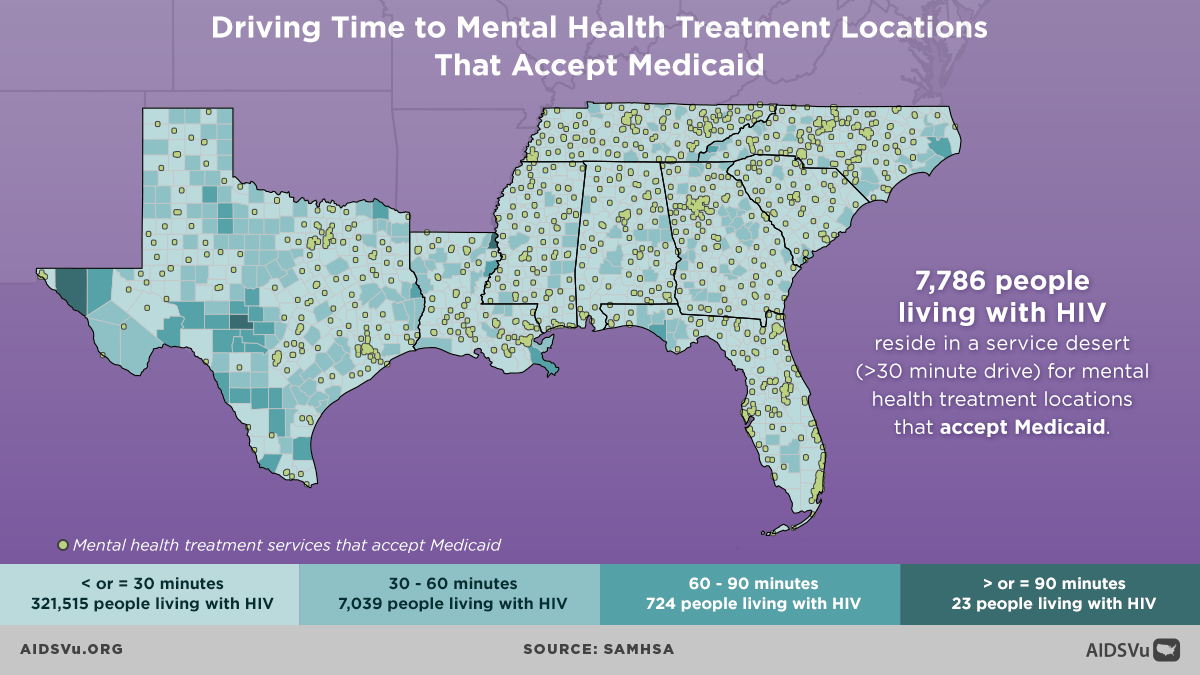

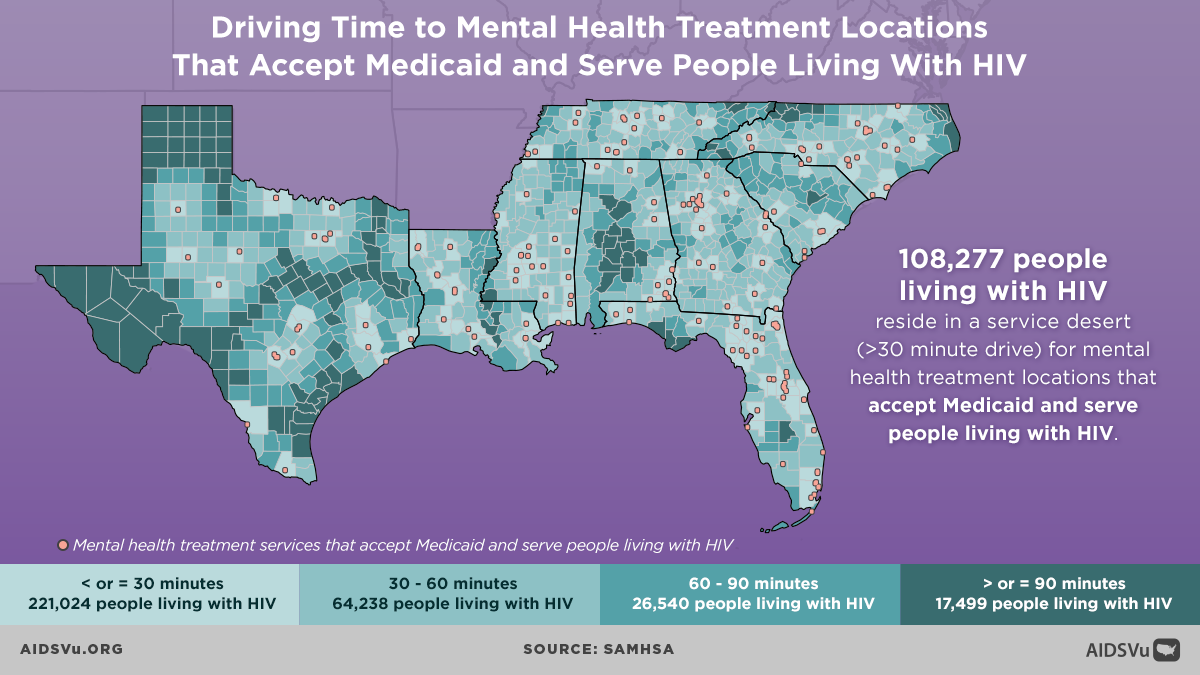

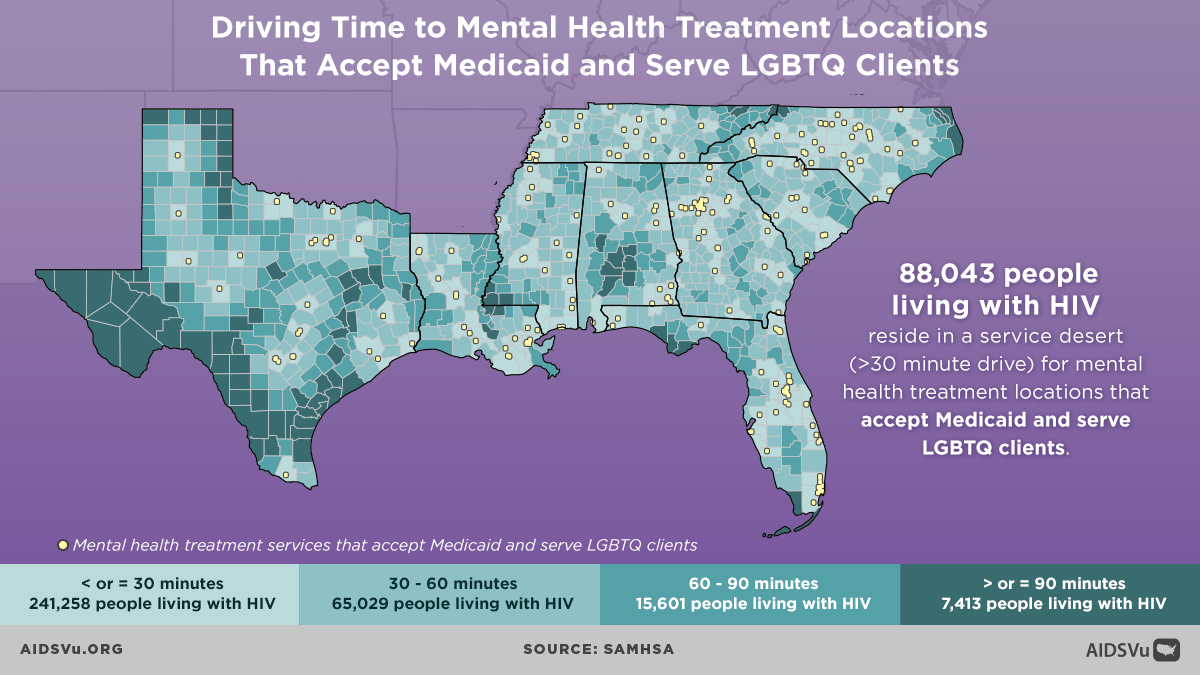

A service desert is a geographic area that does not have access to a key health service. We are defining service deserts as geographic areas, such as a county or a census tract, that have a more than 30-minute one-way drive time to the closest health care service facility. There’s a fair amount of literature behind why we selected the 30-minute cut-off point. A lot of it has to do with just how far individuals are willing to travel for prevention services. Individuals may not want to travel more than that distance, especially if you think about all the added burdens of parking and walking into a clinic. We wanted to understand where the areas are that have limited access to different health services in order to allow for future planning to increase accessibility for those health services.

Our team actually uses Google Maps to determine these service deserts – but in a slightly different way than most people use them. We use a programming interface to conduct thousands of queries very quickly, and look at where services are located in regard to each geographic jurisdictions. After this, the Google Maps interface can give us the estimated drive times for each area. We can then use this information to build a set of maps visualizing the different areas that may lack access to quality health services.

Q: COMPASS recently released new infographics on AIDSVu visualizing drive times to mental health treatment centers that serve people with Medicaid. Why is it important to visualize these service gaps?

In one sense, we could easily provide an enormous spreadsheet of data with just numbers or lists of the geographic areas, indicating whether they were considered a service desert. However, that’s a pretty hard way to digest data. Visuals provide a way for communities to advocate for their needs. They allow for a quick assessment of service availability in their area, and really help us interact with the spaces in which our communities live. These service desert maps serve as a powerful tool to motivate both people in the community and policymakers. These maps provide a quick way for people to clearly communicate what access to services looks like in their area. We are supportive of these mapping efforts because we believe that they convey important information in an abbreviated format that is empowering to communities as well as to those seeking to develop new policies.

We just today completed a year-long data collection process, developing a new database of services for people living with HIV. Currently, the maps that we’re providing depict mental health services and substance abuse services. This new database gives us the ability to create a new set of maps of other services that are also relevant for people living with HIV, such as stigma mitigation services. To our knowledge, it will be the first ever directory of stigma mitigation services for people living with HIV. We have also collected data on harm reduction services that will be able to illustrate where these services are available in COMPASS areas, as well as where to find trauma-informed care.

We look forward to both translating those into service desert maps that illustrate where access is limited, and also to putting them into interactive platforms, like AIDSVu, that allow people who are searching for those kinds of services to figure out where they can access them. That’s coming soon, and we’re very excited about it. We have just recently finished our data collection from over 2,200 clinics.

Q: Can you describe how community-based organizations use these maps to inform their education and advocacy efforts?

For a number of these services, this information may not have been seen before. These maps allow the COMPASS Initiative to think strategically about where resources should be invested. Moreover, they allow our community partners to plan where outreach is needed and where linkage services may be particularly valuable. Visualizing data in this way really helps our team and community partners understand where there are geographic access issues.

The maps can be valuable to view the world from the lived experiences of those who are in need and are trying to seek these services. For instance, some of these maps are limited just to organizations that will accept Medicaid as a payment option. A lot of people live with and rely upon Medicaid. Maps that show service access for folks with these limits helps us as planners consider the reality of the clients and individuals who need to access services like mental health treatment and who can’t go to providers that don’t accept Medicaid. By having maps that look at different types of services, which may vary in accessibility to different groups, it really helps us understand the kind of likely lived experiences of people who are seeking services in distinct areas. This tool provides a deeper level of understanding that I think the community organizations as well as the COMPASS Initiative can use to develop innovative policies and programs.

Q: What are your thoughts on how the COMPASS Initiative and other HIV advocates can make sure ending the HIV epidemic remains a priority for both policymakers and the general public?

I think the COMPASS Initiative is grounded in the belief that engaging with local partners that are a part of the community is a way of investing in sustainable change. That change can’t be centralized – it really must be grassroots. The mission of COMPASS is to provide grants and training to collaboratively embrace this reality and to provide resources for those groups so they can create change in their communities. It’s really a collaborative approach where we leverage our ability to gather new data and to facilitate the scale-up of innovative approaches with the community’s expertise. I think that framework is what will allow us to ensure that these efforts to provide supportive services for people living with HIV remain a priority for policymakers and for all of us, as it should be.