Gina Brown, MSW, is the Community Engagement Manager for Southern AIDS Coalition (SAC)

The Gilead COMPASS Initiative™ (COMmitment to Partnership in Addressing HIV/AIDS in Southern States) is a 10-year, $100 million commitment to support organizations working to address the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the Southern United States.

Q: You have been working in the HIV field for over 15 years. How did you first become involved in community organizing and advocating for better health literacy among people living with HIV (PLWH)?

In 1994, I was diagnosed with HIV. Around this time, I would frequently go to a clinic where they would call you by your full first and last name. Living in New Orleans, I’ve learned that the names here are really unique and often when you hear a name you know the family. One day, they called a woman’s name and I saw every head in the clinic turn around to look at her. I still remember the look on her face – we all knew who her family was.

After I decided to discuss what happened with my doctor and they eventually gave me a phone number to call to report any grievances or recommendations for the clinic. I called the phone number and told the operator the situation and why using a patient’s full name can often be embarrassing and cause unnecessary stigma. Three months later I went to the clinic and when I was in the waiting room my doctor came to the door and she called out Gina B. I looked up and I kind of froze because I couldn’t believe she didn’t call my whole name. When we went into the exam room she said, “I don’t know who you called but the request made sense, so we are no longer able to call patients by their last name.”

That was my first time successfully advocating for those in the HIV community. It took me years to really get into advocacy and community organizing. However, when I did it was around these really important issues. I realized that I was one of those people that could rally my community to come together and advocate for a common goal. So that’s how I knew I had a voice.

Q: You identify as a proud bisexual Black woman living with HIV and have been living with an HIV diagnosis for nearly 30 years. How have you seen stigma in the South for PLWH evolve over the last 30 years? What do we need to do to work towards reducing stigma in the South?

Believe it or not, for all of the years that I’ve been living with HIV, I have not seen that much change from society. Those of us who are living with HIV have evolved ourselves to better stand up against stigma. But as far as the general public, a lot of misinformation is still out there.

People laugh at me whenever I’m doing a training because I say “I’m that woman in the grocery store.” That essentially means someone could be in aisle 3 and I can be on aisle 2, but if you say the wrong thing about HIV, I will have no problem popping over and saying “that’s not true”. I use these moments as opportunities to educate people because I know they simply don’t know the truth. Unfortunately, a lot of the stigma is still here. People still think that you get HIV from a toilet seat, plate, or even an inanimate object. When I hear these statements, I just try and give them the facts.

One thing we can do in the South to combat stigma and start conversations on topics that may be uncomfortable in the Black community is to have it through our churches. A lot of Black people are religious. They go to church and they listen to what their preacher says. If the preacher told them that HIV was a medical condition and not a behavioral condition, I think this would do a lot to reduce the stigma associated with HIV.

I hope this can help our community look beyond the stigma of certain behaviors and start asking other questions. It’s not just the fact that some men have sex with men or women may have sex without a condom. What is their socio-economic status? Are they homeless? Are they a part of the drug injection community? What other things are going on? Since we don’t talk about these things, that stigma stays intact and really hurts our community. However, once you start having those conversations, I think we can get rid of some of that stigma.

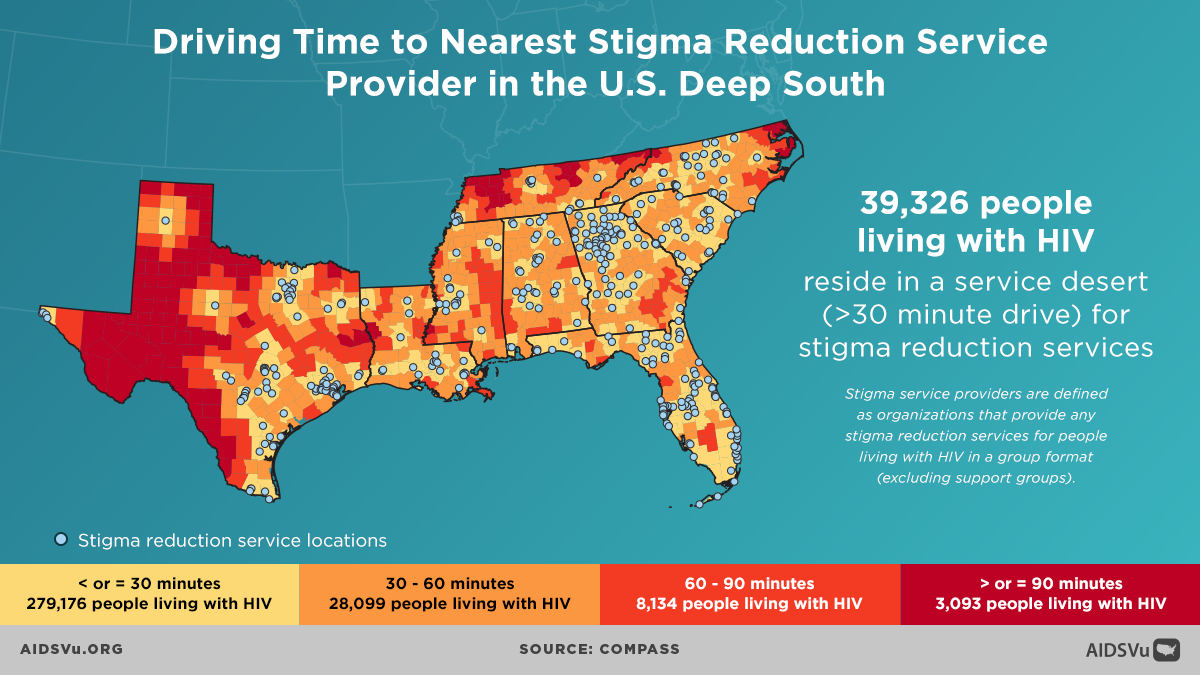

Q: AIDSVu recently spoke with Dr. Aaron Siegler about COMPASS’ project to map different kinds of service deserts across the Deep South. Their research shows that nearly 40,000 PLWH in the Deep South are in a stigma reduction service desert, meaning they are at least a 30-minute drive from a stigma reduction service provider. What does it mean for PLWH to lack access to this kind of service?

It’s huge. These HIV service providers are supposed to be qualified to work with people who have HIV and to make efforts to reduce the stigma surrounding HIV. While many do accomplish this, a lot of providers probably say that’s what they’re doing, but they’re not.

You’re stigmatized from the time you walk into the clinic because it’s not just the provider but the receptionist. Looking at the whole picture, there are so many factors that can contribute to the stigma PLWH face. You have to think about how they’re training their receptionist or the phlebotomist who is drawing your blood. If you have the phlebotomist walking in with a spacesuit on because they know that they are interacting with someone living with HIV, it hurts and these actions matter when we talk about reducing stigma.

Also, when you walk into a clinic and don’t see anyone working there, like the receptionist or phlebotomist, that you feel represents you, it can be an alienating experience for people of color who are living with HIV.

Q: How is SAC working with COMPASS and its other programs to help combat service deserts and reduce stigma among service providers in the Deep South?

Working with SAC, I co-founded a program designed to combat HIV-related stigma called the LEAD (Leadership, Education, and Advocacy Development) Academy. The LEAD Academy seeks to reduce HIV-related stigma by training PLWH to be leaders, educators, and advocates in their communities.

The curriculum was created by and for people living with HIV in the South, and because we created the program, all content is delivered in-person and on-site. This is not a program with a facilitator who says “you know guys, I know how you feel” even though they’re not living with HIV. When we talk about stigma, we’re talking about it from a personal place. This allows us to connect with people and give them the freedom to talk about their fears during the training.

Whatever those fears may be, we try to help them with opening up and facilitating self-disclosure. Because believe it or not, people get their diagnosis and they can’t even say the words “I’m living with HIV.” But how do you stand in the mirror and become comfortable enough to say this out loud? This is the first part of getting rid of any internalized stigma – which can be more debilitating than any external stigma. What people say about me externally means nothing to me. But what I say about myself is everything. When it comes down to it, we are always with ourselves, and we need to figure out how to deal with the layers of internalized stigma. In the LEAD Academy, we walk through those layers. We acknowledge that there are many layers and we can’t get to all of them in our training, but we at least open people up enough to give them the tools to keep exploring.

Additionally, SAC has the Younity Workshop for those who are newly diagnosed with HIV. The Younity Workshop takes those who have never dealt with their diagnosis and uses videos to teach them techniques and skills to reduce internalized HIV-related stigma. So far, the data shows us that 88% of the people who’ve gone through our training have had a positive change in their life.

Q: How does the mapping of service deserts help advocates to get their message across to lawmakers and other individuals in HIV research, funding, and programming? How does it help in focusing attention on the need for more services in the Deep South for PLWH?

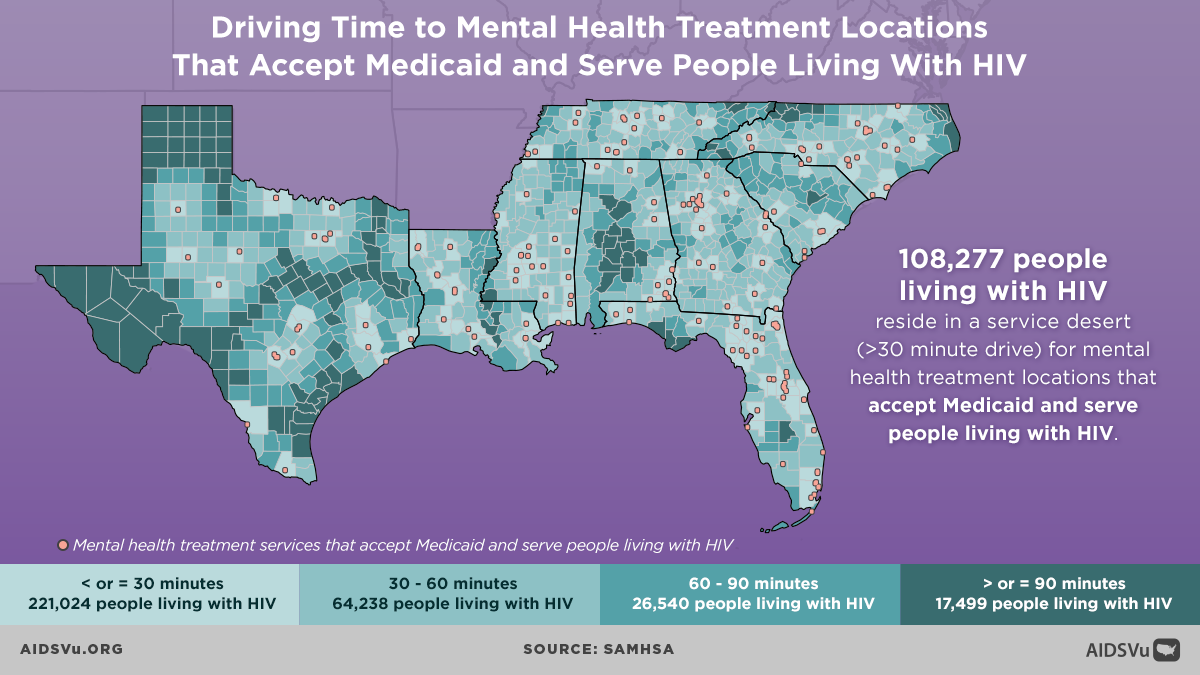

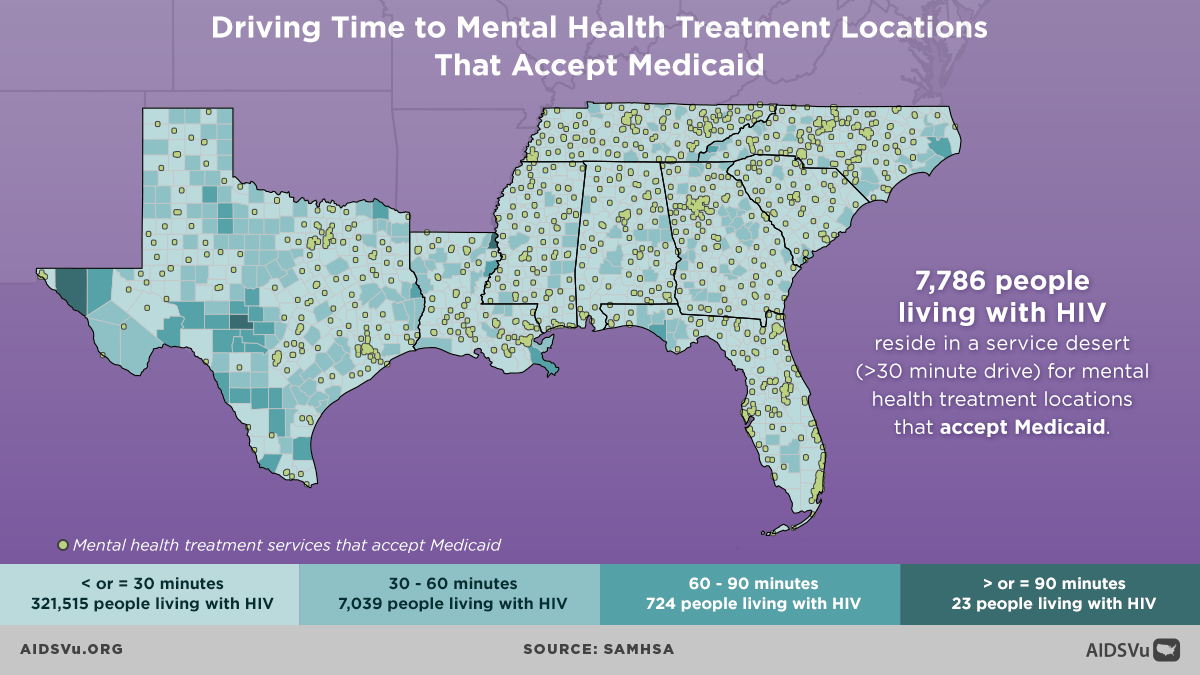

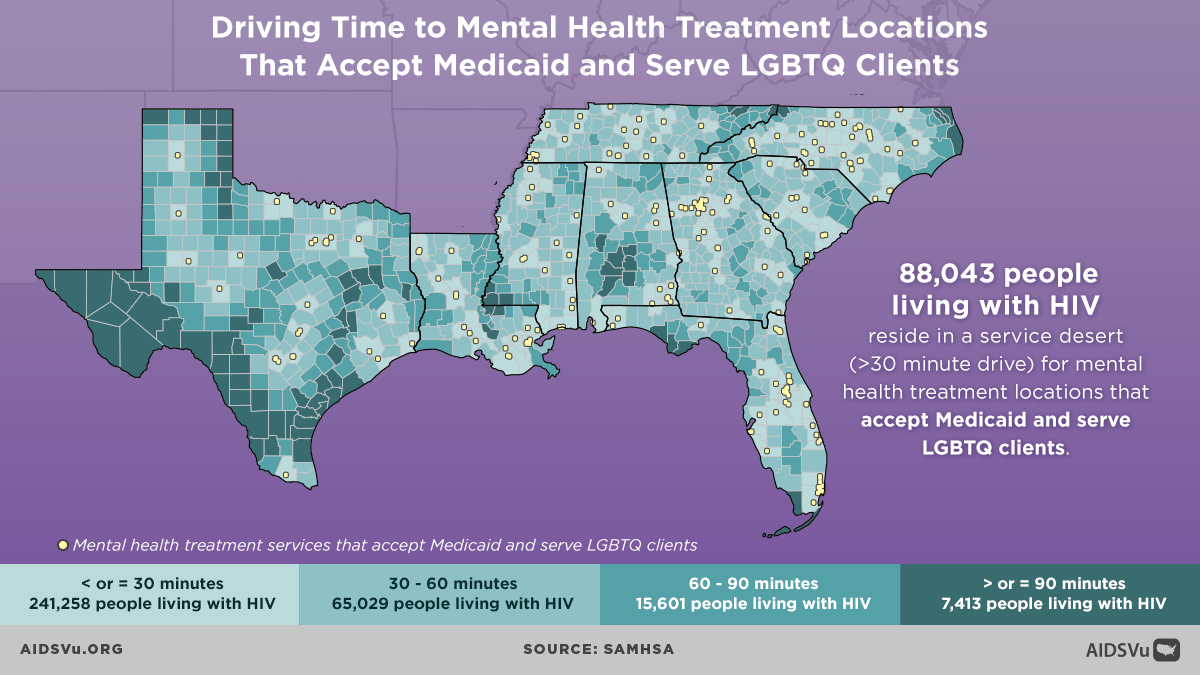

It is a huge help. When we look at that map and can visualize this deficit in services it helps make this problem more concrete and people can see the effect of stigma. Additionally, mapping out these service deserts allows us to communicate this issue to multiple stakeholders who can help. We can get so much more accomplished when we work together, across our disciplines and across our lanes. For example, a policy person could go in and teach people about policy and how to advocate for change. As an organizer, I can get the people in the room. Someone with experience in capacity building can even meet with the providers in an area and communicate what we can change.

It’s going to take an all-hands-on-deck approach. I hope we look at the COMPASS maps and feel empowered to make a difference. I hope we teach people how to advocate for themselves even when we’re not there. The beauty of these maps as tools is we know somebody in local, state, and the federal government from every area. That really helps to get resources into any given area when you see that there are no providers within 50 miles.

I think these maps are great advocacy tools and I look forward to using them in the future. We keep hearing about the push to end the HIV epidemic, however, we’re not going to end it if people are still stigmatized. That is why it is so important to identify those people who may not be getting their needs met and are living in areas with resource deficits.

A note from Dr. Aaron Siegler, Director of Geospatial Core and an Associate Professor in the Department of Behavioral Sciences and Health Education at Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health.

It is exciting to see a community leader and advocate, Gina Brown, using the data collected by our COMPASS team. For this work, we contacted over 3,000 HIV and LGBTQ service provider organizations through phone calls and offered them participation in a survey to assess the landscape of HIV support services in the US South. Relevant to this post, we asked organizations whether they provide HIV stigma reduction services that in a group format, which is the gold standard for stigma mitigation service. We then mapped providers of group stigma mitigation services, and assessed service deserts by looking at driving distances to care, using methodology similar to a paper we recently published in the American Journal of Public Health.