Sonia Canzater, JD, MPH, Senior Associate, oversees the Hepatitis Policy Project at Georgetown University Law Center’s O’Neill Institute for National & Global Health Law

Jeffrey S. Crowley, MPH, is the Program Director of Infectious Disease Initiatives at Georgetown University Law Center’s O’Neill Institute for National & Global Health Law

Q: Mr. Crowley, you have been working in HIV for most of your career and you led the development of the country’s first domestic National HIV/AIDS Strategy, which focuses in part on reducing HIV-related health disparities. Why do you think it is important that the country focuses on the intersection between HIV and other health disparities, particularly Hepatitis C infection?

Jeff Crowley: We have been working for decades trying to end the HIV epidemic and that effort centers around controlling the HIV virus itself. Even as new technologies come into play, my goal remains for people living with HIV to lead long, happy, and healthy lives. Our community’s broader agenda has always been about helping people, whether by addressing housing stability or making sure people have enough food to eat, for example.

However, we didn’t do all this work to only prevent or treat people with HIV infection. We don’t want them to become sick or die from other health conditions. We must focus on all the co-morbidities associated with HIV itself while also responding to co-occurrent conditions like Hepatitis C. This is important because right now we have a real opportunity to eliminate Hepatitis C among those living with HIV in the United States.

Q: Ms. Canzater, your career has focused on the intersection of law and public health. How has the opioid epidemic impacted your work to address HIV and Hepatitis C among people who inject drugs (PWID)?

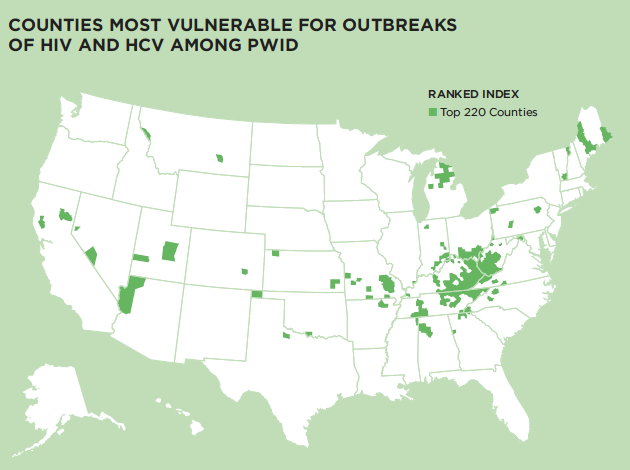

Sonia Canzater: The opioid epidemic – as it relates to the sharing and reuse of unsterile needles, syringes, and injection equipment – has caused the high rates of Hepatitis C that we’ve seen during the past decade, as well as HIV outbreaks in states like Indiana and Massachusetts. Our current focus needs to be on improving the health of drug users and their access to care. To help address this, much of my work focuses on the legal and policy barriers impeding efforts to improve the health of PWID and people with substance use disorder so that we can move toward elimination.

At the O’Neill Institute, we recently launched an addiction and public policy initiative to examine policies that impede access to care. For example, many state Medicaid programs still require evidence of sobriety, some with a minimum year of sobriety, before they authorize Hepatitis C treatment for anyone with a history of drug use. Even now, many jurisdictions have laws that criminalize the possession of needles and syringes without a prescription. In addition, slow progress on policy implementation is often rooted in misinformation, a lack of awareness, and stigma related to substance use disorder – associated illnesses such as Hepatitis C and HIV. Our Hepatitis Policy Project aims to raise awareness about co-infection and provide resources for the public, policymakers, and advocates.

Q: You are both co-authors of the new brief, “Eliminating Hepatitis C Among People Living With HIV in the United States: Leveraging the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program to Move Us Forward.” Why do you believe that the Ryan White Program has a central role to play in eliminating Hepatitis C among people living with HIV?

Jeff Crowley: The Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program provides health care to uninsured and underinsured people with HIV. It serves roughly 500,000 people with HIV and is the third-largest payer of medical care for people living with HIV in the country, just behind Medicaid and Medicare. However, what’s often forgotten or less understood about Ryan White’s role is its ability to emphasize HIV treatment.

For example, Medicaid is the largest source of funding for HIV care in the US yet it serves well under one million people with HIV, out of more than 72 million beneficiaries. The Ryan White program is unique in that we not only have a source of payment for services, but we also have critical expertise as the program is solely focused on people living with HIV. This is critically important because as we know, just because a cure or treatment is available, does not mean the disease will automatically be eliminated. To get to elimination, there must be a targeted, conscientious plan in place and expertise to implement it.

Sonia Canzater: Ryan White is a long-standing successful program and it is very important to leverage it to expand into improving screening and treatment for Hepatitis C. As the brief states, one in four people with HIV will be coinfected with Hepatitis C at some point in their lives. In states like Indiana and Massachusetts that have experienced HIV outbreaks, 90% of those with HIV also passed on their current Hepatitis C infections. The two diseases frequently come in tandem for certain populations, which is why it is critical that we utilize as many resources as we can to reach out and make sure people receive the care and services they need.

Q: What is currently being done to address co-infection within the Ryan White Program and how would leveraging the program help to better achieve Hepatitis C elimination in this population?

Jeff Crowley: One of the most important things that the Ryan White Program has done is work with the leadership of the HIV/AIDS Bureau at Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) to allow for Ryan White to pay for Hepatitis C treatment for people living with HIV.

The program’s leadership has adopted a jurisdictional approach, in a sense, to say, “How do we develop the right models of care to actually move towards elimination for an entire community?” Many clinical providers think about the impact of care on an individual with Hepatitis C. However, by adopting a jurisdictional focus, I believe it is going to inherently broaden the focus to larger scale of treatment for Hepatitis C.

Sonia Canzater: We also must ensure that there is a standard practice of rescreening. There is a very high rate of initial screening for Hepatitis C in the Ryan White Program, but to make sure that risk behaviors are identified and monitored, we must enforce a standardized procedure for rescreening for those at increased risk throughout the program

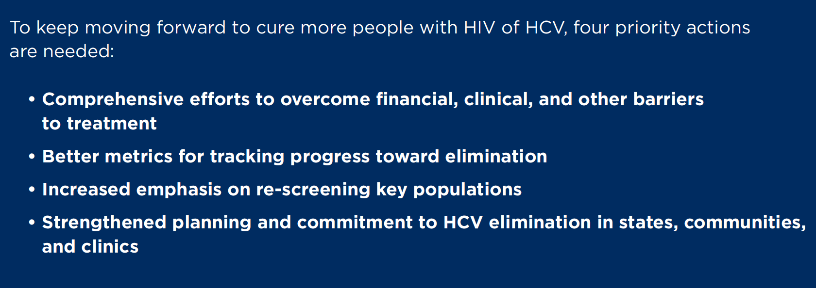

Q: In the brief, you outline four priority actions that you recommend the Ryan White Program take. If the Ryan White Program moved forward with these four actions, what kind of impact do you believe that would have on the risk for Hepatitis C among those living with HIV?

Jeff Crowley: The way I think about it is that we are not going to just declare that we can eliminate Hepatitis C, and then the HIV population naturally wakes up and is also focused on eliminating Hepatitis C. If we are going to eliminate Hepatitis C in the US, we are going to do it through targeting certain populations and programs.

We are excited about the progress taking place in the Veteran’s Administration and within the Ryan White Program. We see people adopting strategic approaches, jurisdictions developing elimination plans, and the implementation of increased rescreening. When we do all of these things, some of our leading jurisdictions start to show that they have been or are able to diminish or even eliminate Hepatitis C in their communities. This, in turn, can inspire other jurisdictions to do the same.

We also try and highlight places that are making major progress toward elimination. New York City is experiencing a major decline in HIV new infections, in part because the city has implemented a small number of strategic priorities. Many academic initiatives tried to do the same type of core activity to build on that progress; that is what I’m hoping to see with Hepatitis C.

Sonia Canzater: Identifying those programs and those strategies has been very effective in being able to disseminate information to other areas. Standardizing outcomes throughout the Ryan White Program would be ideal so that every program has the kind of outcomes that we see in places like New York.