Understanding Health Equity and Disparities

Health equity represents the state in which everyone has a fair and just opportunity to attain their highest level of health. Achieving this requires ongoing societal efforts to address historical and contemporary injustices, overcome economic and social obstacles to healthcare, and eliminate preventable health disparities. In the context of HIV, health equity means that factors like race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, geographic location, or socioeconomic status should not determine someone’s risk of acquiring HIV or their ability to access quality prevention, testing, treatment, and care services.

Health disparities are differences in the incidence, prevalence, and mortality of diseases that exist among specific population groups. These disparities reflect systematic inequities in the social, economic, and environmental conditions that shape health outcomes. For HIV, these disparities are particularly pronounced and persistent, creating patterns where certain communities bear disproportionate burdens of infection, illness, and death despite decades of advances in prevention and treatment.

The relationship between health disparities and HIV is both cause and consequence. Social determinants of health create conditions that increase HIV vulnerability, while HIV diagnosis can exacerbate existing inequities through stigma, discrimination, and the economic burden of managing a chronic illness. Understanding these complex relationships is essential for developing effective interventions that address both immediate health needs and underlying structural factors.

Social Determinants of Health: The Root Causes

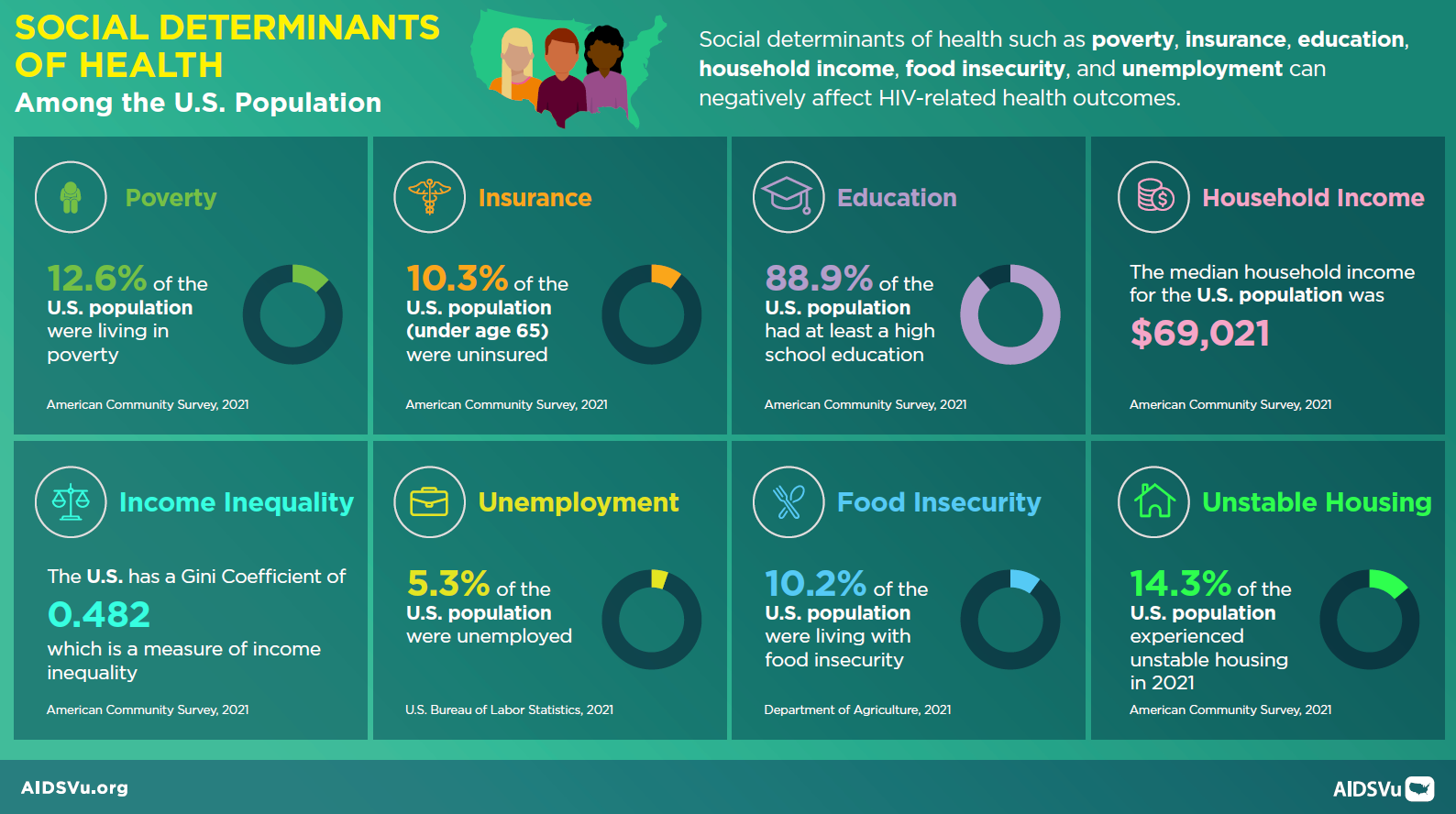

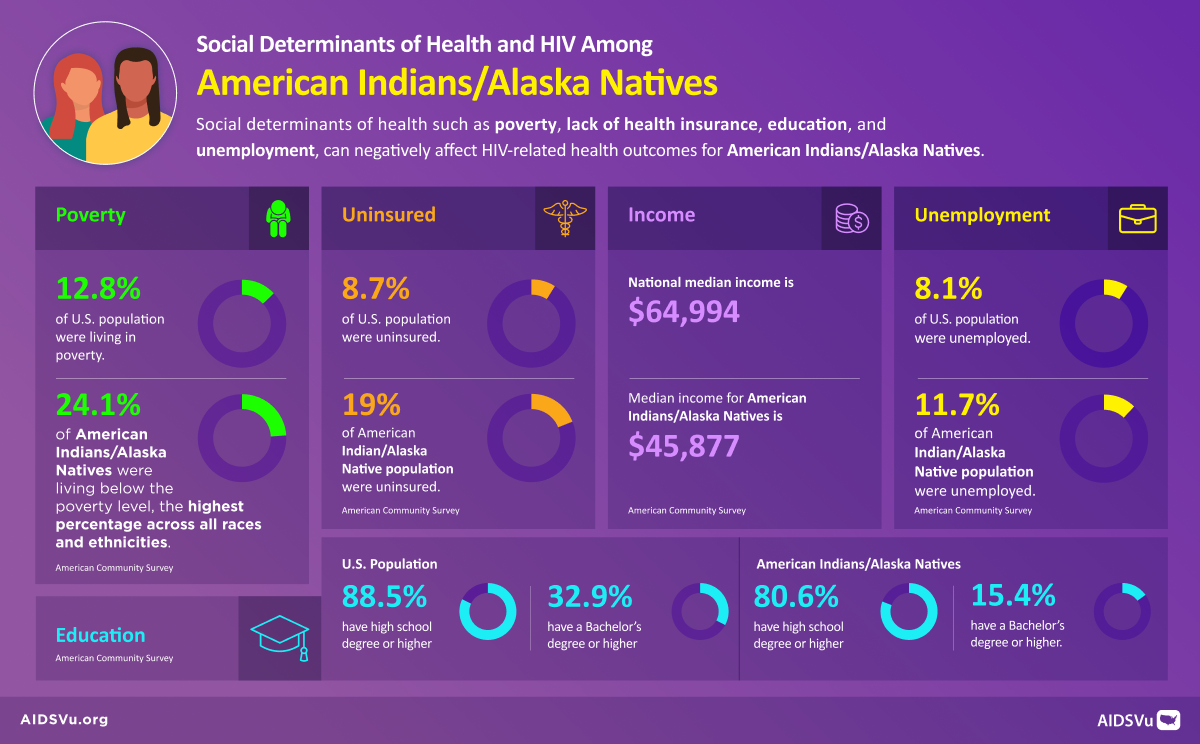

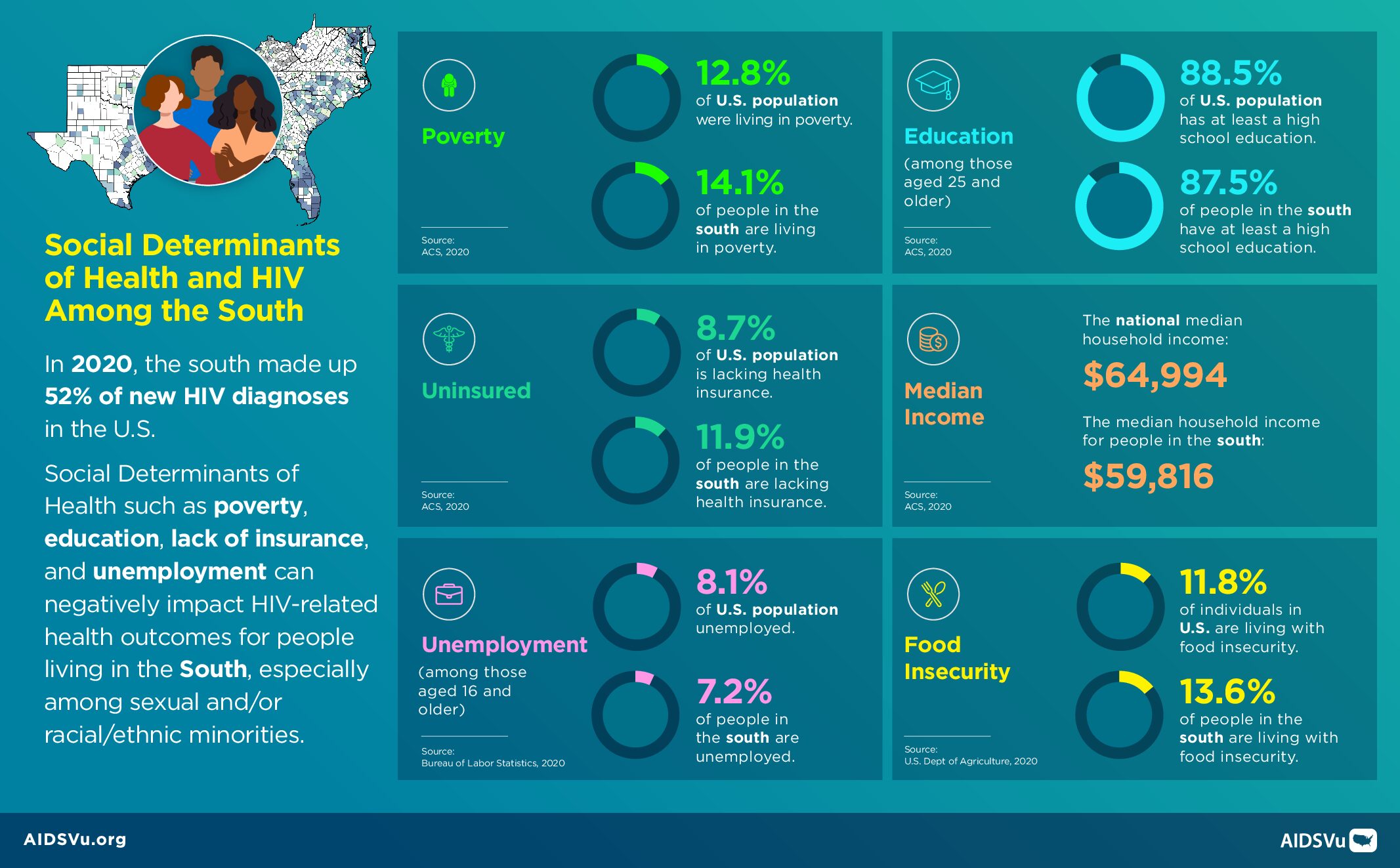

Social determinants of health are the conditions in which people live, learn, work, play, and worship that fundamentally shape health outcomes. These determinants operate at multiple levels, from individual circumstances to community conditions to policy environments that either support or undermine health. For HIV, social determinants create the context within which transmission occurs and determine access to prevention and care services.

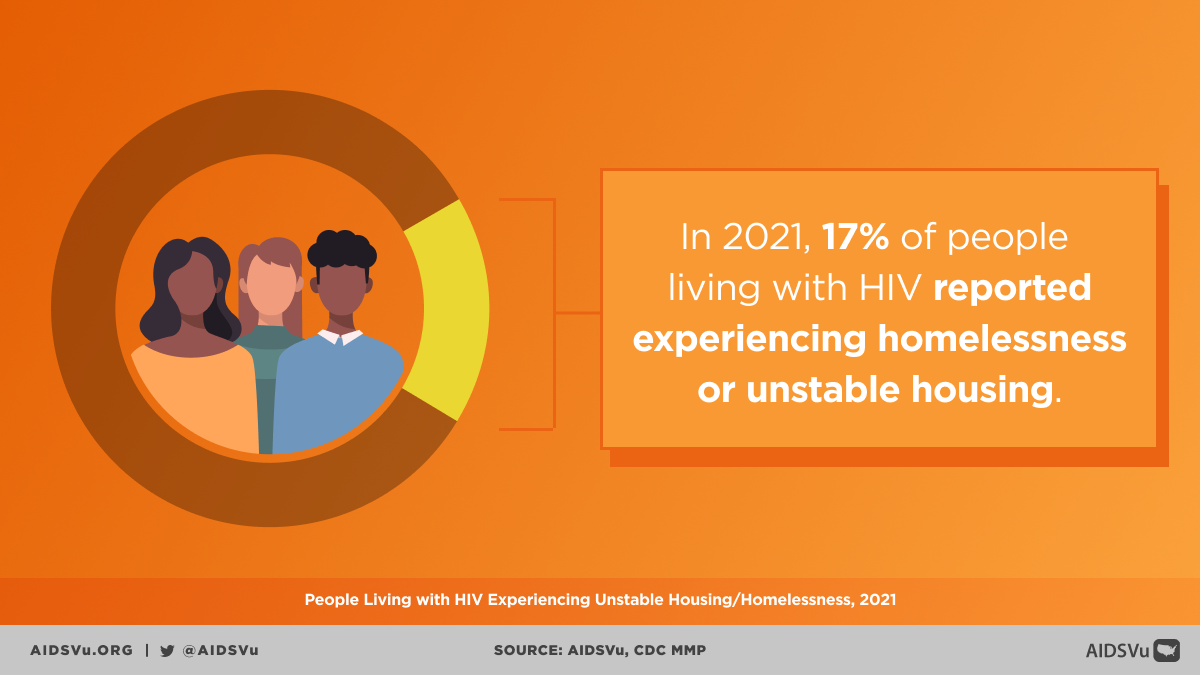

Economic stability serves as a foundational determinant, influencing HIV risk through multiple pathways. Poverty can increase HIV vulnerability by limiting housing stability, creating food insecurity, reducing access to healthcare, and constraining people’s ability to prioritize long-term health over immediate survival needs. Economic disadvantage also affects the ability to negotiate safer sexual practices and can push people into situations that may increase HIV risk, such as survival sex work or sharing injection equipment.

Healthcare access and quality represent another critical domain of social determinants. Lack of health insurance, limited availability of culturally competent providers, and geographic barriers to care all affect HIV prevention and treatment outcomes. In communities with limited healthcare infrastructure, people may delay HIV testing, receive fragmented care, or struggle to maintain consistent treatment regimens.

Educational opportunities influence HIV outcomes through multiple mechanisms, including health literacy, economic opportunities, and social networks. Limited educational attainment can reduce awareness of HIV prevention strategies, limit ability to navigate complex healthcare systems, and restrict economic opportunities that might reduce HIV vulnerability.

Racial and Ethnic Disparities: Persistent and Profound

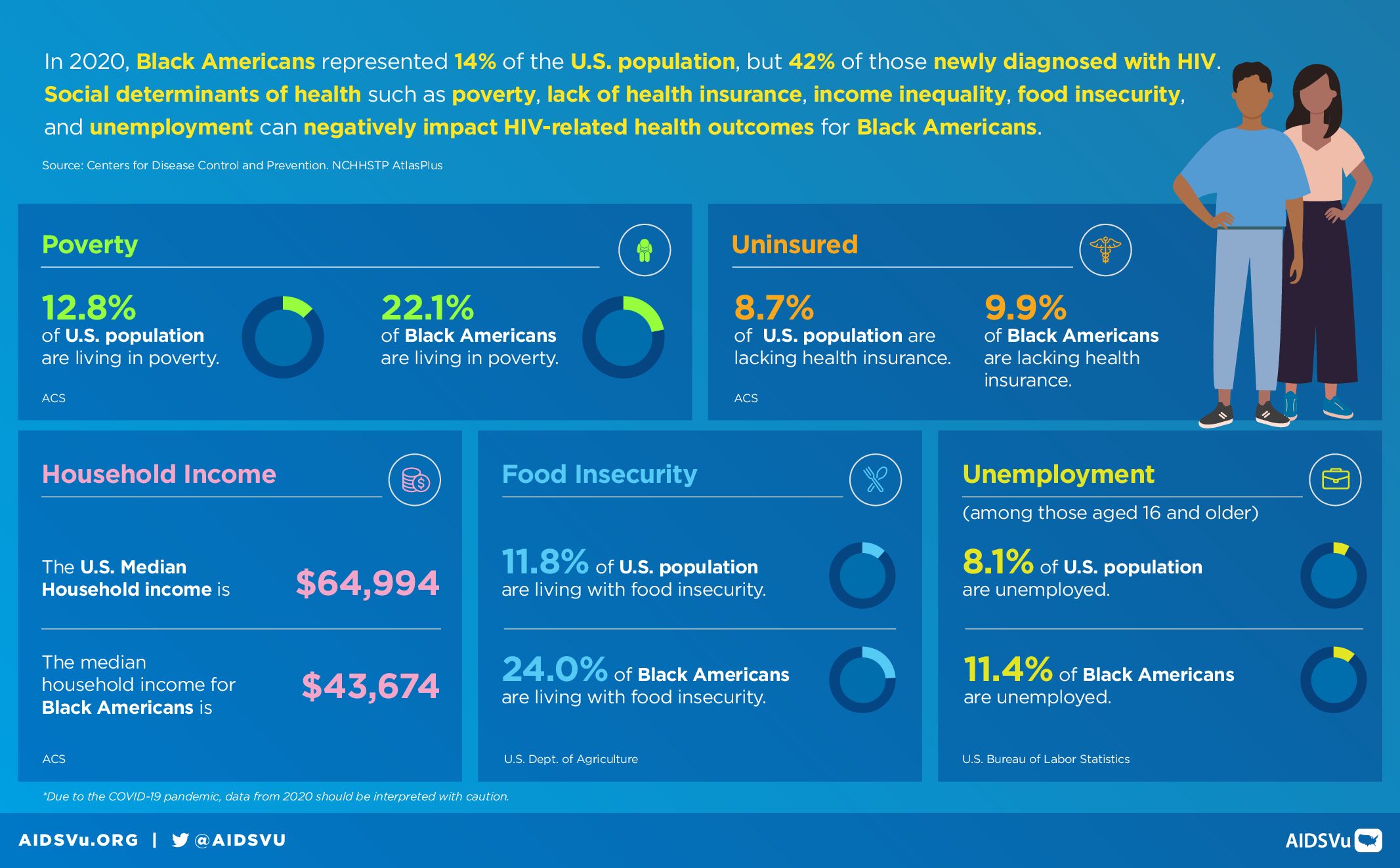

HIV-related health disparities among racial and ethnic minorities remain among the most persistent and profound inequities in American healthcare. These disparities reflect the cumulative impact of structural racism, historical trauma, and ongoing discrimination that create conditions of vulnerability while limiting access to resources and opportunities that support health.

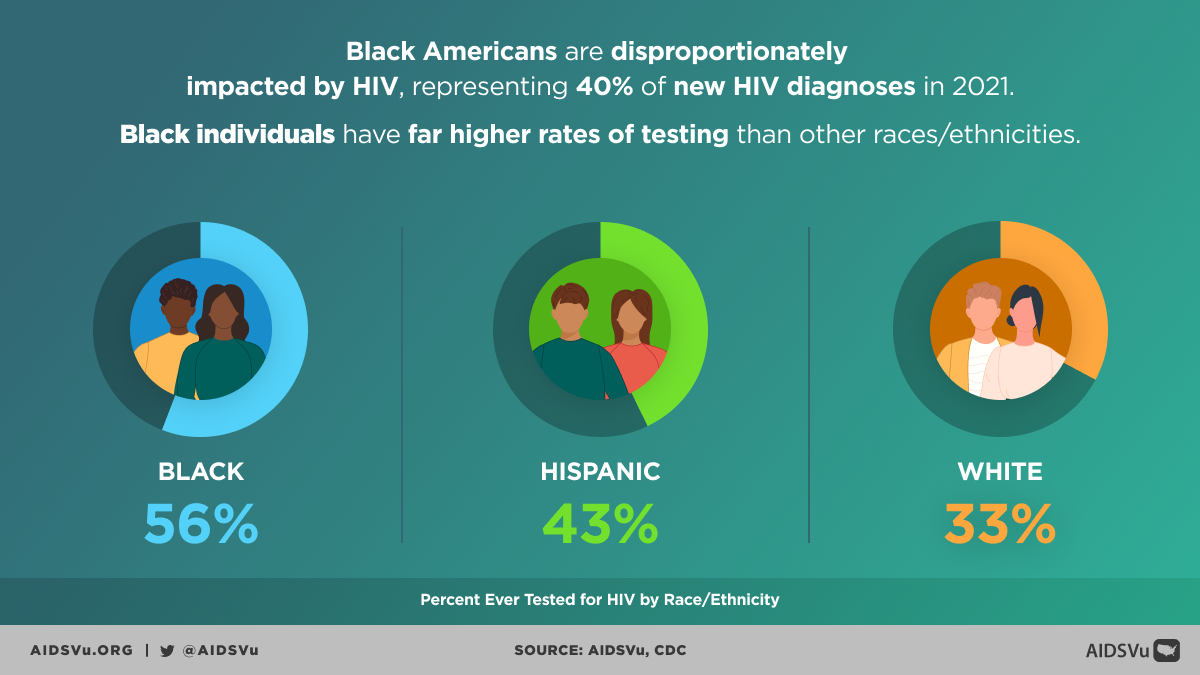

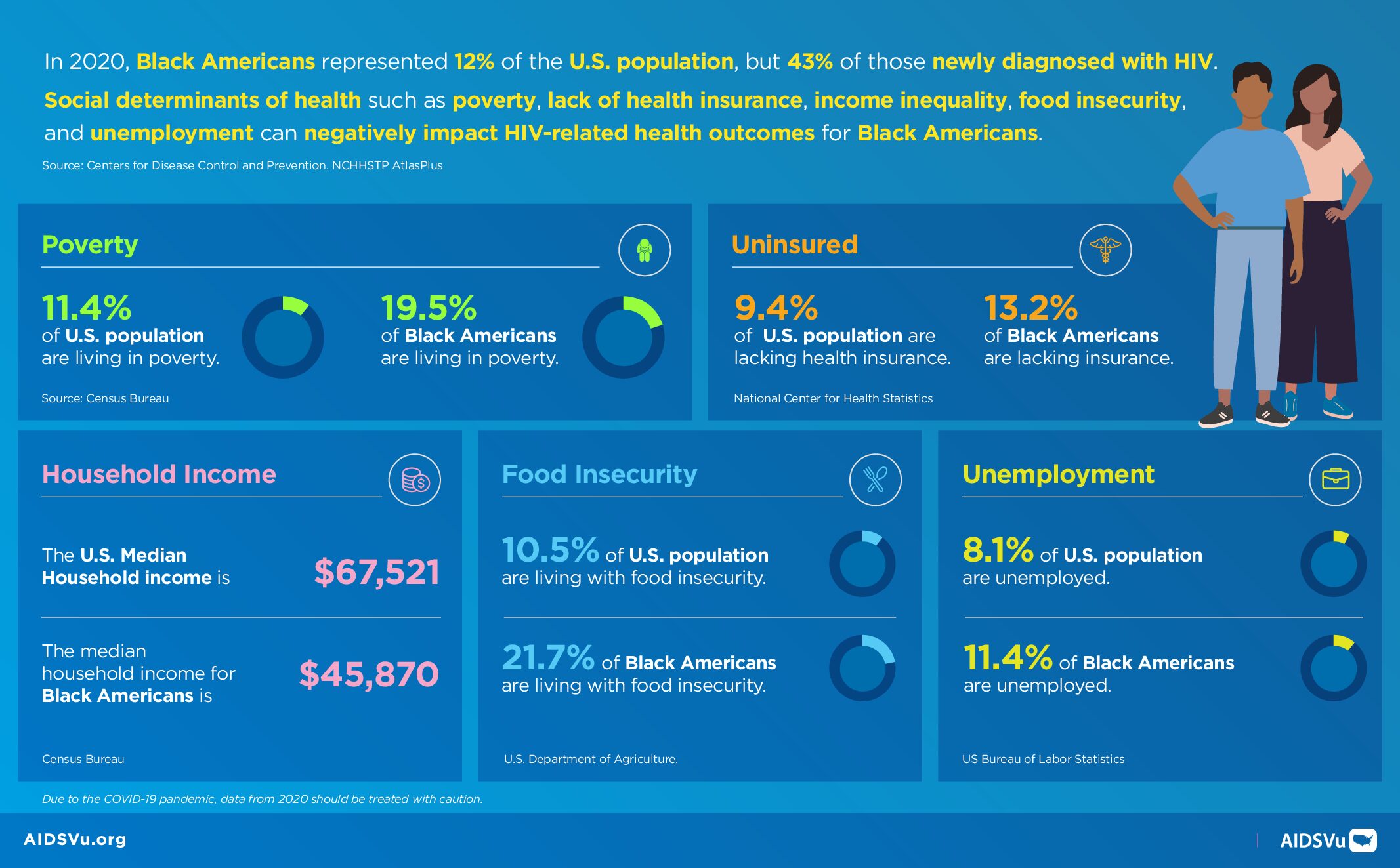

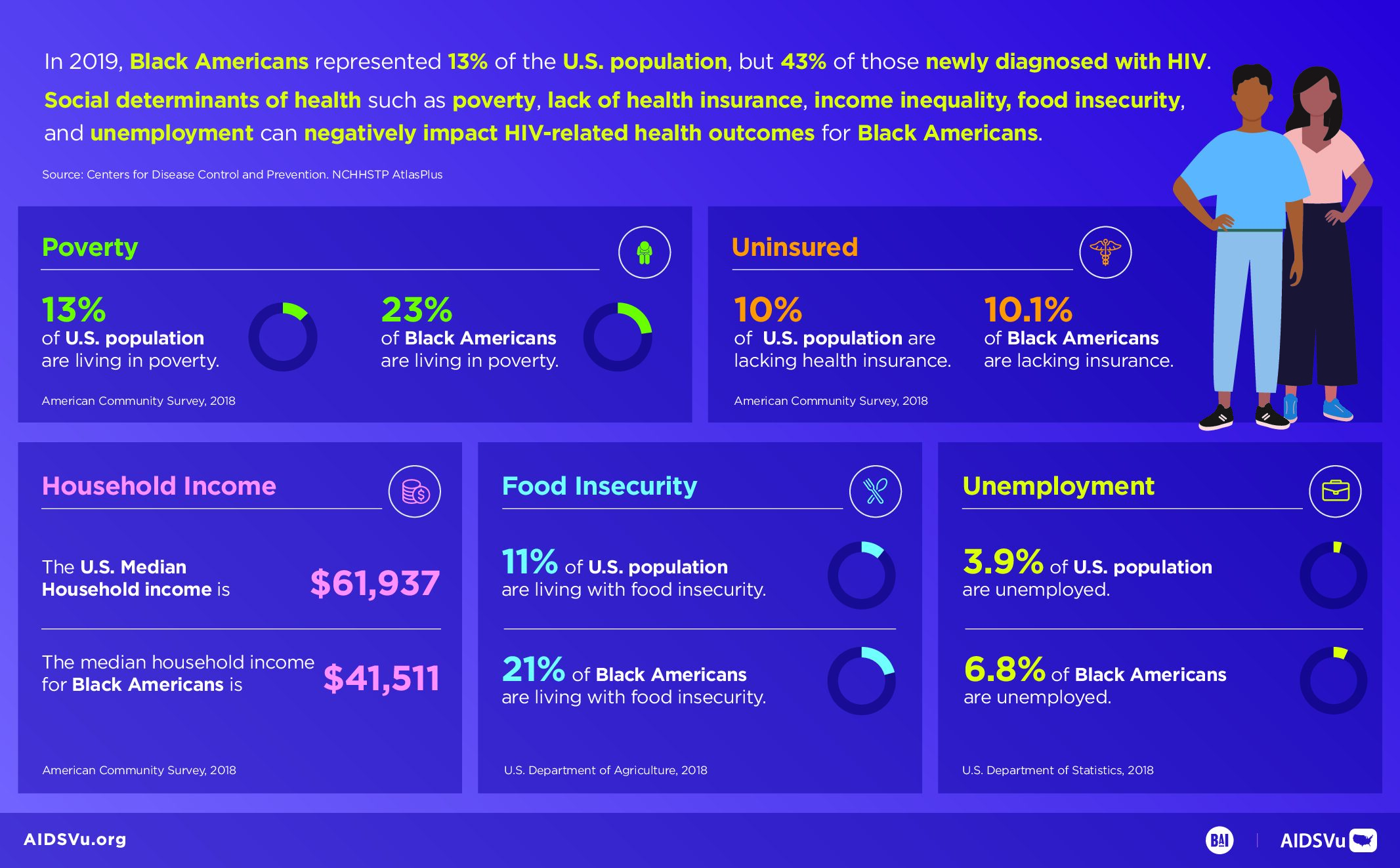

Black Americans experience the most severe HIV disparities of any racial or ethnic group in the United States. Despite representing only 12% of the population, Black people accounted for 38% of new HIV diagnoses in 2022 and 40% of all people living with HIV. The diagnosis rate among Black Americans (41.6 per 100,000) is approximately eight times higher than among white Americans (5.3 per 100,000). These disparities persist across the HIV care continuum, with Black people less likely to achieve optimal outcomes at each stage from testing through viral suppression.

Hispanic/Latinx/Latine people also face significant HIV disparities that have been worsening over time. While representing 18% of the U.S. population, Hispanic/Latinx/Latine people accounted for 32% of new HIV diagnoses in 2022. HIV diagnoses among Hispanic/Latinx/Latine people increased by 17% between 2018 and 2022, even as overall diagnoses remained stable. The diagnosis rate among Hispanic/Latinx/Latine people (23.4 per 100,000) is more than four times higher than among white Americans.

These racial and ethnic disparities in HIV cannot be explained by individual behaviors or genetic factors. Instead, they reflect the impact of structural racism that has created and maintained inequitable access to education, employment, housing, healthcare, and other resources that affect health outcomes. Historical policies including residential segregation, discriminatory lending practices, and exclusion from social safety net programs have created neighborhood and community conditions that influence HIV risk and access to care.

The Intersection of Multiple Identities

HIV disparities often reflect the intersection of multiple identities and social positions, creating compound vulnerabilities that require nuanced understanding and response. The experience of a Black gay man differs from that of a white gay man or a Black heterosexual woman, reflecting how racism, homophobia, and other forms of discrimination interact to create unique patterns of risk and resilience.

For LGBTQ+ communities, HIV disparities reflect the intersection of sexual and gender minority stress with other forms of discrimination. Gay and bisexual men continue to bear the highest burden of HIV, accounting for 67% of all new diagnoses in 2022 despite representing a small percentage of the population. Within this population, racial and ethnic minorities face compound challenges, with Black and Hispanic/Latinx/Latine gay and bisexual men experiencing higher rates of infection and poorer care outcomes compared to their white counterparts.

Gender intersects with other identities to create distinct patterns of HIV vulnerability. Women face different risks and barriers compared to men, with heterosexual transmission being the primary route of infection among women. Black women, in particular, face the intersection of racism and sexism that creates specific vulnerabilities including limited ability to negotiate safer sexual practices, economic dependence on male partners, and healthcare discrimination that affects both HIV prevention and care.

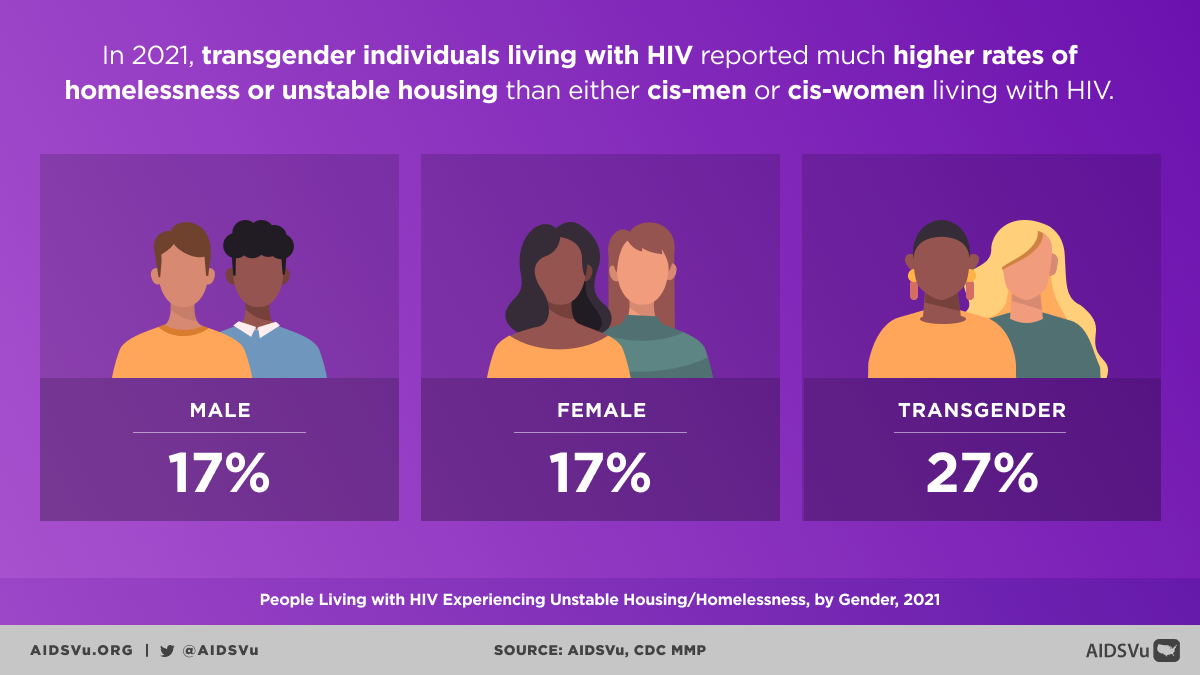

Transgender individuals, particularly transgender women of color, experience extraordinarily high rates of HIV that reflect the intersection of transphobia, racism, and other forms of marginalization. Limited employment opportunities, housing discrimination, healthcare barriers, and high rates of violence create environments where HIV transmission is more likely while limiting access to prevention and care services.

Cultural and Linguistic Barriers

Cultural factors and language barriers create additional layers of complexity in addressing HIV disparities. In some cultural contexts, discussions of sexuality and sexual health may be considered taboo, making HIV prevention education and open communication about risk factors more difficult. Cultural beliefs about illness, treatment, and healthcare may influence help-seeking behaviors and treatment adherence.

Language barriers can prevent effective communication about HIV prevention, testing, and treatment, particularly when healthcare settings lack adequate interpretation services or culturally appropriate materials. These barriers may be particularly pronounced for immigrant communities, who may also face concerns about immigration status that prevent them from accessing healthcare services.

Religious and spiritual beliefs can both complicate and support HIV prevention and care efforts. While some religious interpretations may contribute to stigma around behaviors associated with HIV transmission, many faith traditions also emphasize compassion, healing, and social justice in ways that can support people affected by HIV. Effective HIV programming often involves working with religious and community leaders to address stigma while building on existing sources of community support.

Healthcare System Factors

Healthcare systems themselves contribute to HIV disparities through multiple mechanisms including provider bias, structural barriers, and limited cultural competency. Research consistently documents that healthcare providers may hold implicit biases that affect their interactions with patients from different racial, ethnic, sexual, or gender minority backgrounds. These biases can influence clinical decision-making, quality of communication, and patient experiences in ways that affect health outcomes.

Structural barriers within healthcare systems include limited availability of culturally competent services, inadequate interpretation services, inflexible scheduling systems, and geographic maldistribution of HIV specialists. These barriers can prevent people from accessing care or receiving optimal treatment, contributing to poorer outcomes among already marginalized populations.

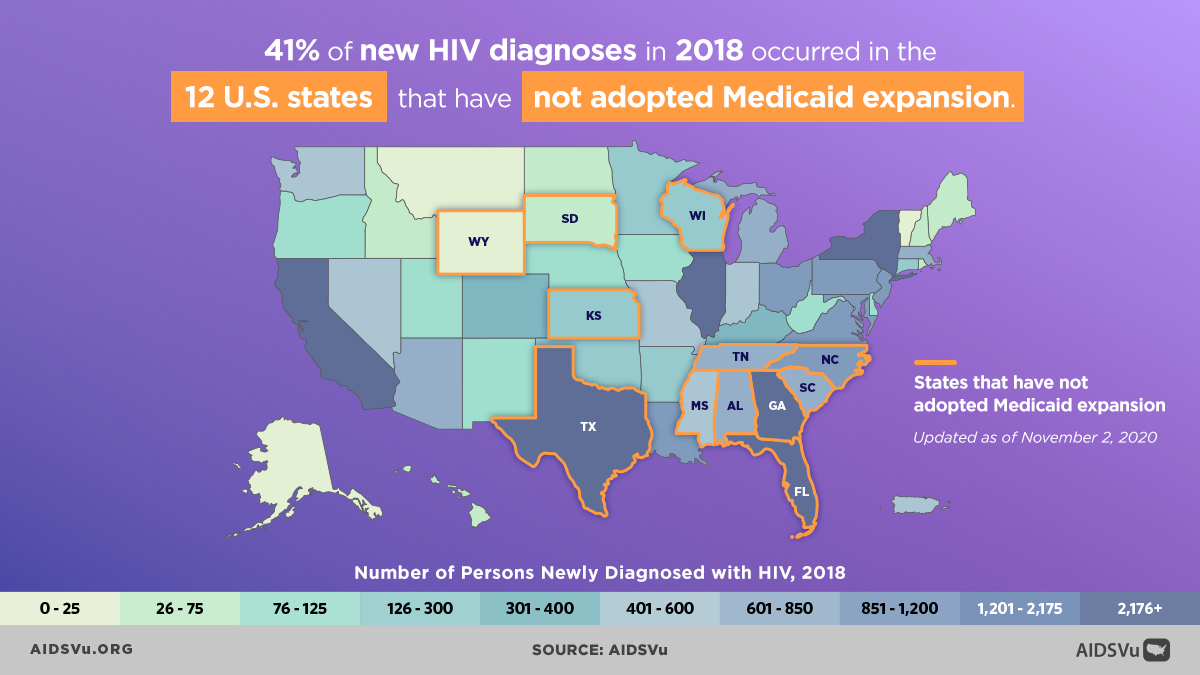

Healthcare financing systems also contribute to disparities, with uninsured and underinsured individuals facing significant barriers to accessing HIV prevention, testing, and treatment services. The concentration of uninsured individuals in certain geographic areas and demographic groups creates systematic disparities in access to care that directly affect HIV outcomes.

Mental Health and Psychosocial Factors

Mental health challenges both contribute to and result from HIV disparities, creating complex feedback loops that require comprehensive attention. People facing multiple forms of discrimination and marginalization experience chronic stress that affects both mental health and immune function, potentially increasing HIV susceptibility and affecting treatment outcomes.

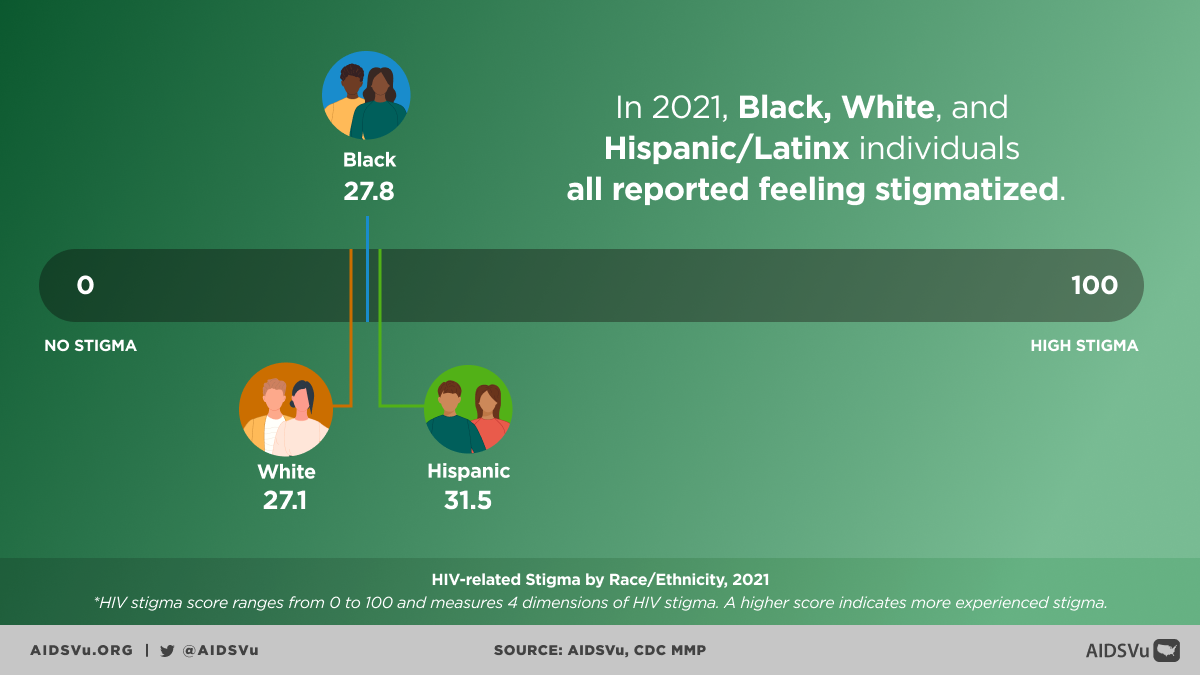

Stigma represents a particularly important psychosocial factor that affects HIV disparities at multiple levels. HIV-related stigma can prevent people from seeking testing, delay entry into care, interfere with treatment adherence, and limit disclosure to sexual partners. This stigma often intersects with other forms of stigma related to sexual orientation, gender identity, race, and drug use, creating compound barriers to prevention and care.

Mental health services are often inadequately integrated with HIV care, despite strong evidence for the importance of addressing mental health in HIV treatment. People from marginalized communities may face additional barriers to accessing mental health services, including provider bias, cultural incompetence, and limited availability of culturally appropriate services.

Geographic Disparities and Rural Challenges

Geographic location significantly influences HIV disparities, with rural areas and certain urban neighborhoods experiencing particular challenges in HIV prevention and care. Rural communities often lack HIV specialists, have limited public transportation options, and may have cultural environments that are less accepting of populations most affected by HIV.

The concentration of HIV services in urban areas creates access barriers for rural residents, who may need to travel long distances for specialized care. This geographic barrier can delay diagnosis, interfere with treatment continuity, and prevent access to newer prevention technologies like PrEP.

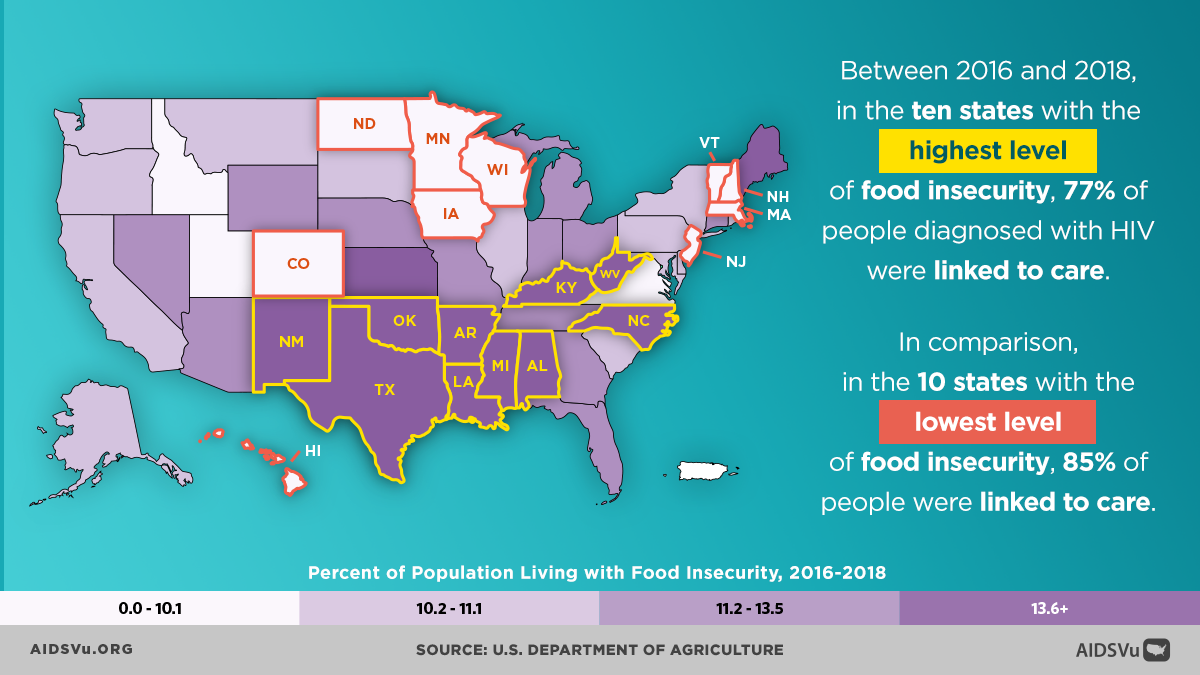

Regional differences in policy environments also contribute to geographic disparities in HIV outcomes. States that have not expanded Medicaid, for example, have higher uninsured rates and more limited access to HIV care, contributing to poorer outcomes in those areas. Similarly, states with fewer civil rights protections for LGBTQ+ individuals may have environments that are less conducive to seeking HIV-related services.

The Role of Criminalization and Incarceration

The criminal justice system creates and perpetuates HIV disparities through multiple pathways including HIV criminalization laws, mass incarceration policies, and the intersection of criminal justice involvement with other forms of marginalization. HIV criminalization laws, which exist in many states, can deter people from seeking testing and care due to fears that positive status could be used against them legally.

Mass incarceration disproportionately affects communities of color and creates disruptions in social networks, economic opportunities, and healthcare continuity that can increase HIV vulnerability. People with histories of incarceration face barriers to employment, housing, and healthcare that can affect long-term HIV outcomes.

The criminalization of drug use and sex work also contributes to HIV disparities by pushing these activities underground and creating barriers to accessing harm reduction services. Fear of law enforcement can prevent people who inject drugs from accessing syringe services programs, and criminalization of sex work can prevent sex workers from negotiating safer working conditions or accessing healthcare.

Data and Surveillance Challenges

Understanding and addressing HIV disparities requires high-quality data that can capture the experiences of different population groups. However, current surveillance systems have significant limitations that may obscure certain disparities or provide incomplete pictures of HIV’s impact on marginalized communities.

Traditional surveillance categories may not adequately capture the diversity within racial and ethnic groups, potentially masking important disparities. For example, data on Hispanic/Latinx/Latine people are often not disaggregated by country of origin, immigration status, or primary language, potentially obscuring important differences in HIV risk and outcomes within this diverse population.

Surveillance of transgender and gender non-conforming populations has been particularly limited, with many systems only recently beginning to collect data on gender identity separate from sex assigned at birth. This data limitation has contributed to the invisibility of transgender people in HIV programming and resource allocation.

AIDSVu’s Social Determinants Mapping

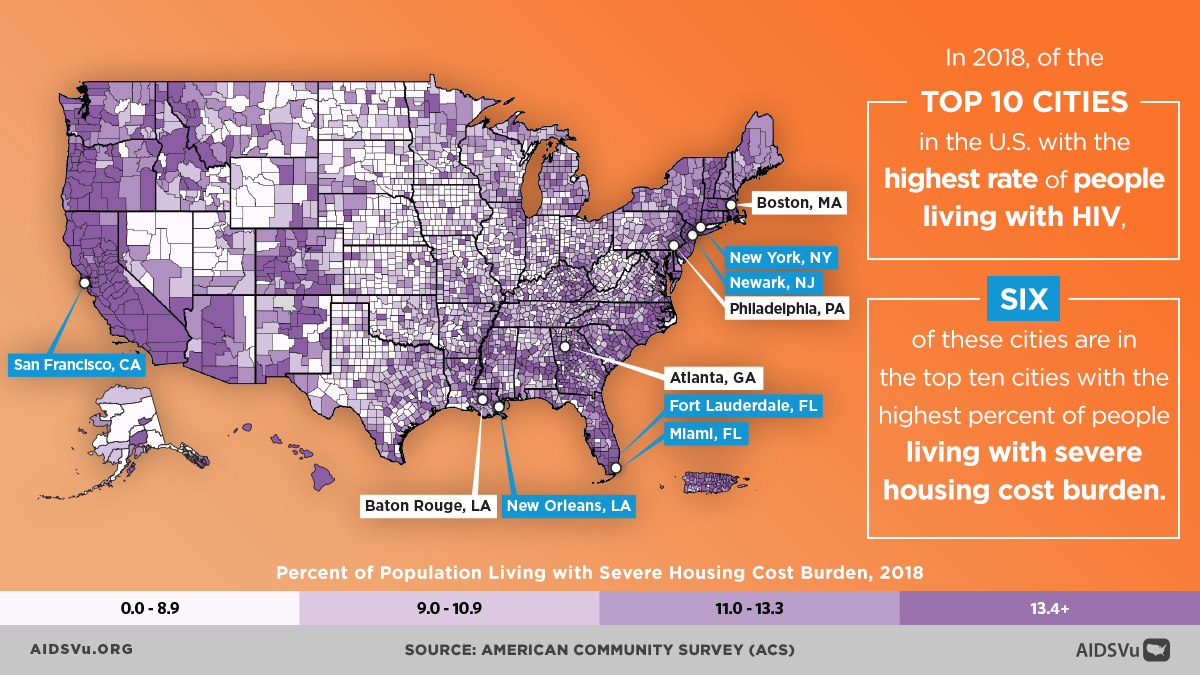

To help users understand the relationship between HIV and social determinants of health, AIDSVu provides interactive maps that allow users to examine HIV data alongside key social and economic indicators. These tools enable researchers, advocates, and policymakers to visualize how factors like poverty, education, housing, and healthcare access correlate with HIV outcomes at the county level.

The mapping platform includes indicators such as food insecurity, high school education completion, housing burden, income inequality, median household income, Medicaid expansion status, uninsured rates, poverty, and unemployment. Users can overlay these indicators with HIV prevalence, new diagnoses, mortality, and PrEP utilization data to explore relationships and identify areas where interventions might have the greatest impact.

AIDSVu also displays maps of related infectious diseases including hepatitis C and syphilis, recognizing that these conditions often co-occur with HIV and share similar social determinants. This integrated approach helps users understand HIV within the broader context of health disparities and infectious disease patterns.

Moving Toward Health Equity

Addressing HIV disparities requires comprehensive approaches that go beyond individual-level interventions to address the structural factors that create and maintain health inequities. This includes policy changes that expand access to healthcare, education, economic opportunities, and safe housing, while also addressing discrimination and bias in healthcare and other systems.

Healthcare system changes are needed to improve cultural competency, eliminate bias, and ensure that services are accessible and appropriate for all communities. This includes training providers in cultural humility, diversifying the healthcare workforce, and implementing policies that promote equity in care delivery.

Community-centered approaches that involve affected communities in program design, implementation, and evaluation are essential for developing interventions that are culturally responsive and effective. These approaches recognize that communities possess important knowledge and assets that can inform solution development while building local capacity for advocacy and change.

Policy advocacy remains crucial for addressing the structural factors that drive HIV disparities. This includes advocating for Medicaid expansion, civil rights protections, criminal justice reform, and other policy changes that can improve social determinants of health and reduce barriers to HIV prevention and care.

Research and evaluation efforts must continue to examine disparities while also documenting effective approaches to reducing them. This includes research that examines intersectionality, community-based participatory research approaches, and evaluation of interventions specifically designed to address health equity.

The pursuit of health equity in HIV requires sustained commitment from all sectors of society, recognizing that health disparities are not inevitable but rather the result of policies and practices that can be changed. Only through comprehensive approaches that address both immediate health needs and underlying structural inequities can we achieve the goal of ending the HIV epidemic for all communities.

5 Ways to Use AIDSVu

View local statistics

National-, state-, and city-level profiles including data on social determinants of health.

Learn MoreExplore maps

Interactive maps including social determinants of health and other comparison maps.

Learn MoreShare infographics

Infographics presenting insights on the social determinants of health mapped on AIDSVu.

Learn MoreFor More Information

Learn more about the health disparities and HIV with these resources.